113-) English Literature

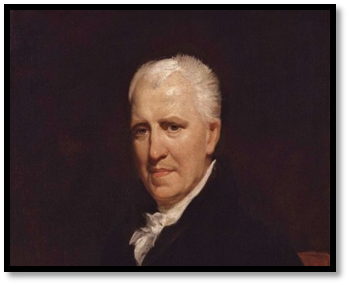

George Crabbe

1754–1832

George

Crabbe was born in 1754 in the village of Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England. He

apprenticed to a doctor at the age of 14 but left his village and medical

career in 1780 to pursue his literary interests in London. With the help of

Edmund Burke, Crabbe published The Library (1781) and became a clergyman.

Writing out of the Augustan tradition, he used primarily heroic couplets. In

The Village (1783), he eschewed idealized visions of pastoral life and

portrayed the hardships of rural poverty. His poem The Borough (1810) included

realistic descriptions of characters in a village. His other collections of

poetry include The Newspaper (1785), Tales in Verse (1812), and Tales of the

Hall (1819).

Crabbe

worked as a clergyman in Leicestershire and Suffolk and was a longtime opium

user. Byron and the Romantic poets admired his poetry, as did Jane Austen.

Benjamin Britten based his opera Peter Grimes on a character from The Borough.

Crabbe died in 1832.

George

Crabbe

George

Crabbe (/kræb/ KRAB; born December 24, 1754, Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England—died

February 3, 1832, Trowbridge, Wiltshire) 24 December 1754 – 3 February 1832)

was an English poet, surgeon and clergyman. He is best known for his early use

of the realistic narrative form and his descriptions of middle and

working-class life and people .George Crabbe English writer of poems and verse

tales memorable for their realistic details of everyday life.

Biography

Early

life

Crabbe

was born in Aldeburgh, Suffolk, the eldest child of George Crabbe Sr. The elder

George Crabbe had been a teacher at a village school in Orford, Suffolk, and

later in Norton, near Loddon, Norfolk; he later became a tax collector for salt

duties, a position that his own father had held. As a young man he married

an older widow named Craddock, who became the mother of his six children:

George, his brothers Robert, John, and William, his sister Mary, and another

sister who died as an infant.

George

Crabbe was born on Christmas Eve, 1754 in the town of Aldeburgh, Suffolk.

Having been a teacher, George’s father was keen to encourage his son to take an

interest in literature and fed him passages from the likes of John Milton on a

regular basis. He soon developed an interest in, and talent for, writing but

his first career choice was to be a surgeon. He had studied Latin and the

classics at Stowmarket school and, on leaving, tried to forge a medical career.

He also kept the company of other young men who all had an interest in

literature and, in 1772, he entered and won a poetry writing prize. This was

his first published work. Others followed with the same magazine that had run

the competition.

In

truth his early years were a struggle. At one time he even worked as a warehouseman

and he found himself constantly in debt, with little hope of repaying them.

Fortunately though his friends didn’t desert him and he managed to keep going

with their help. His friendship with Edmund Burke gave him his first major

break; Burke put him forward for the position of Chaplain to the Duke of

Rutland and here began a long association with this noble family. Having made

little headway in his medical career path to date, he found much more success

as a clergyman and, eventually, as a poet. In the 1770s, Crabbe began his

career as a doctor's apprentice, later becoming a surgeon. In 1780, he

travelled to London to make a living as a poet. After encountering serious

financial difficulty and being unable to have his work published, he wrote to

the statesman and author Edmund Burke for assistance. Burke was impressed

enough by Crabbe's poems to promise to help him in any way he could. The two

became close friends and Burke helped Crabbe greatly both in his literary

career and in building a role within the church.

Burke

introduced Crabbe to the literary and artistic society of London, including Sir

Joshua Reynolds and Samuel Johnson, who read The Village before its publication

and made some minor changes. Burke secured Crabbe the important position of Chaplain

to the Duke of Rutland. Crabbe served as a clergyman in various capacities for

the rest of his life, with Burke's continued help in securing these positions.

He developed friendships with many of the great literary men of his day,

including Sir Walter Scott, whom he visited in Edinburgh, and William

Wordsworth and some of his fellow Lake Poets, who frequently visited Crabbe as

his guests.

Lord

Byron described him as "nature's sternest painter, yet the best."

Crabbe's poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets, and has been

described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society. The

modern critic Frank Whitehead wrote that "Crabbe, in his verse tales in

particular, is an important—indeed, a major—poet whose work has been and still

is seriously undervalued." Crabbe's works include The Village (1783),

Poems (1807), The Borough (1810), and his poetry collections Tales (1812) and

Tales of the Hall (1819).

George

Crabbe was an English poet, clergyman, surgeon and entomologist who, with the

help of some influential friends, established himself as a writer of substance.

His work was not, at first, popular but with subsequent revisions, and the

patronage of well-known literary figures such as Edmund Burke, Samuel Johnson

and William Wordsworth (and many others), Crabbe made his mark as a poet. He

also produced novels but these were of much lower quality than his poems. His

best known works were the epic pieces The Village, published in 1783, and The

Borough (1810). These were powerful, well written pieces that portrayed the

lives of the ordinary people living in either rural locations or the bigger,

more populated towns that were springing up on the back of industrialisation.

He

had sent samples of his work (such as The Village) to his friend Burke and this

led to introductions to the likes of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Samuel Johnson.

Publication followed of work that had previously been rejected by publishers

and Crabbe found himself in a better situation than he had ever been before.

His appointment with the Duke of Rutland soon followed and, although he had

some difficulties with other members of the household, the Duke and Duchess

took Crabbe to their hearts and his future was thus secured.

The

Village received the following praise from Samuel Johnson (in a letter to Sir

Joshua Reynolds:

George

Jr. spent his first 25 years close to his birthplace. He showed an aptitude for

books and learning at an early age. He was sent to school while still very

young, and developed an interest in the stories and ballads that were popular

among his neighbours. His father owned a few books, and used to read passages

from John Milton and from various 18th-century poets to his family. He also

subscribed to Benjamin Martin's Philosophical Magazine, giving the "poet's

corner" section to George. The senior Crabbe had interests in the local

fishing industry, and owned a fishing boat; he had contemplated raising his son

George to be a seaman, but soon found that the boy was unsuited to such a career.

George's

father respected his son's interest in literature, and George was sent first to

a boarding-school at Bungay near his home, and a few years later to a more

important school at Stowmarket, where he gained an understanding of mathematics

and Latin, and a familiarity with the Latin classics. His early reading

included the works of William Shakespeare, Alexander Pope, who had a great

influence on George's future works, Abraham Cowley, Sir Walter Raleigh and

Edmund Spenser. He spent three years at Stowmarket before leaving school to

find a medical apprenticeship.

In

1768 Crabbe was apprenticed to an apothecary at Wickhambrook , near Bury St

Edmunds; the apothecary also kept a small farm, and he ended up doing farm

labour and errands, rather than medical work. In 1771 he changed masters and

moved to Woodbridge. There he was under the surgeon John Page. He remained

until 1775.

While

at Woodbridge, Crabbe joined a small club of young men who met at an inn for

evening discussions. Through his contacts there he met his future wife, Sarah

Elmy. Crabbe called her "Mira", later referring to her by this name

in some of his poems. During this time he began writing poetry. In 1772, a

ladies' magazine offered a prize for the best poem on the subject of hope, which

Crabbe won. The same magazine printed other short pieces of Crabbe's throughout

1772. They were signed "G. C., Woodbridge," and included some of his

lyrics addressed to Mira. Other known verses written while he was at Woodbridge

show that he made experiments in stanza form modelled on the works of earlier

English poets, but only showed some slight imitative skill.

1775

to 1785

His

first major work, a satirical poem of nearly 400 lines in Pope's couplet form

entitled Inebriety, was self-published in 1775. Crabbe later said of the poem,

which received little or no attention at the time, "Pray let not this be

seen ... there is very little of it that I'm not heartily ashamed of." By

this time he had completed his medical training and had returned home to

Aldeburgh. He had intended to go on to London to study at a hospital, but he

was forced through low finances to work for some time as a local warehouseman.

He eventually travelled to London in 1777 to practise medicine, returning home

in financial difficulty after a year. He continued to practise as a surgeon

after returning to Aldeburgh, but as his surgical skills remained deficient, he

attracted only the poorest patients, and his fees were small and undependable.

This hurt his chances of an early marriage, but Sarah stayed devoted to him.

In

late 1779 he decided to move to London and see if he could make it as a poet,

or, if that failed, as a doctor. He moved to London in April 1780, where he had

little success, and by the end of May he had been forced to pawn some of his

possessions, including his surgical instruments. He composed a number of works

but was refused publication. He wrote several letters seeking patronage, but

these were also refused. In June Crabbe witnessed instances of mob violence

during the Gordon Riots, and recorded them in his journal. He was able to

publish a poem at this time entitled The Candidate, but it was badly received

by critics.

He

continued to rack up debts that he had no way of paying, and his creditors

pressed him. He later told Walter Scott and John Gibson Lockhart that

"during many months when he was toiling in early life in London he hardly

ever tasted butchermeat except on a Sunday, when he dined usually with a

tradesman's family, and thought their leg of mutton, baked in the pan, the

perfection of luxury." In early 1781 he wrote a letter to Edmund Burke

asking for help, in which he included samples of his poetry. Burke was swayed

by Crabbe's letter and a subsequent meeting with him, giving him money to

relieve his immediate wants, and assuring him that he would do all in his power

to further Crabbe's literary career. Among the samples that Crabbe had sent to

Burke were pieces of his poems The Library and The Village.

A

short time after their first meeting Burke told his friend Sir Joshua Reynolds

that Crabbe had "the mind and feelings of a gentleman." Burke gave

Crabbe the footing of a friend, admitting him to his family circle at

Beaconsfield. There he was given an apartment, supplied with books, and made a

member of the family. The time he spent with Burke and his family helped by

enlarging his knowledge and ideas, and introducing him to many new and valuable

friends including Charles James Fox and Samuel Johnson. He completed his

unfinished poems and revised others with the help of Burke's criticism. Burke

helped him have his poem, The Library, published anonymously in June 1781, by a

publisher that had previously refused some of his work. The Library was greeted

with modest praise from critics, and slight public appreciation.

Through

their friendship, Burke discovered that Crabbe was more suited to be a

clergyman than a surgeon. Crabbe had a good knowledge of Latin and an evident

natural piety, and was well read in the scriptures. He was ordained to the

curacy of his native town on 21 December 1781 through Burke's recommendation.

He returned to live in Aldeburgh with his sister and father, his mother having

died in his absence. Crabbe was surprised to find that he was poorly treated by

his fellow townsmen, who resented his rise in social class. With Burke's help,

Crabbe was able to leave Aldeburgh the next year, to become chaplain to the

Duke of Rutland at Belvoir Castle in Leicestershire. This was an unusual move

on Burke's part, as this kind of preferment would usually have been given to a

family member or personal friend of the Duke or through political interest.

Crabbe's

experience as chaplain at Belvoir was not altogether happy. He was treated with

kindness by the Duke and Duchess, but his slightly unpolished manners and his

position as a literary dependent made his relations with others in the Duke's

house difficult, especially the servants. However, the Duke and Duchess and

many of their noble guests shared an interest in Crabbe's literary talent and

work. During his time there, his poem The Village was published in May 1783,

achieving popularity with the public and critics. Samuel Johnson said of the

poem in a letter to Reynolds "I have sent you back Mr. Crabbe's poem,

which I read with great delight. It is original, vigorous, and elegant."

Johnson's friend and biographer James Boswell also praised The Village. It was

said at the time of publication that Johnson had made extensive changes to the

poem, but Boswell responded by saying that "the aid given by Johnson to

the poem, as to The Traveller and Deserted Village of Goldsmith, were so small

as by no means to impair the distinguished merit of the author."

Crabbe

was able to keep up his friendships with Burke, Reynolds, and others during the

Duke's occasional visits to London. He visited the theatre, and was impressed

with the actresses Sarah Siddons and Dorothea Jordan. Around this time it was

decided that, as Chaplain to a noble family, Crabbe was in need of a college

degree, and his name was entered on the boards of Trinity College, Cambridge,

through the influence of Bishop Watson of Llandaff, so that Crabbe could obtain

a degree without residence. This was in 1783, but almost immediately afterwards

he received an LL.B. degree from the Archbishop of Canterbury. This degree

allowed Crabbe to be given two small livings in Dorsetshire, Frome St Quintin

and Evershot. This promotion does not seem to have interfered with Crabbe's

residence at Belvoir or in London; it is likely that curates were placed in

these situations.

On

the strength of these preferments and a promise of future assistance from the

Duke, Crabbe and Sarah Elmy were married in December 1783, in the parish church

of Beccles, where Miss Elmy's mother lived, and a few weeks later went to live

together at Belvoir Castle. In 1784 the Duke of Rutland became Lord Lieutenant

of Ireland. It was decided that Crabbe was not to be on the Duke's staff in

Ireland, though the two men parted as close friends. The young couple stayed on

at Belvoir for nearly another eighteen months before Crabbe accepted a vacant

curacy in the neighbourhood, that of Stathern in Leicestershire, where Crabbe

and his wife moved in 1785. A child had been born to them at Belvoir, dying

only hours after birth. During the following four years at Stathern they had

three other children; two sons, George and John, in 1785 and 1787, and a

daughter in 1789, who died in infancy. Crabbe later told his children that his

four years at Stathern were the happiest of his life.

1785

to 1810

In

October 1787 the Duke of Rutland died at the Vice-Regal Lodge in Dublin, after

a short illness, at the early age of 35. Crabbe assisted at the funeral at

Belvoir. The Duchess, anxious to have their former chaplain close by, was able

to get Crabbe the two livings of Muston, Leicestershire, and Allington,

Lincolnshire, in exchange for his old livings. Crabbe brought his family to

Muston in February 1789. His connection with the two livings lasted for over 25

years, but during 13 of these years he was a non-resident. He stayed three

years at Muston. Another son, Edmund, was born in 1790. In 1792, through the

death of one of Sarah's relations and soon after of her older sister, the

Crabbe family came into possession of an estate in Parham in Suffolk, which

removed all of their financial worries . Crabbe soon moved his family to this

estate. Their son William was born the same year.

Crabbe's

life at Parham was not happy. The former owner of the estate had been very

popular for his hospitality, while Crabbe's lifestyle was much more quiet and

private. His solace here was the company of his friend Dudley Long North and

his fellow Whigs who lived nearby. Crabbe soon sent his two sons George and

John to school in Aldeburgh. After four years at Parham, the Crabbes moved to a

home in Great Glemham, Suffolk, placed at his disposal by Dudley North. The

family remained here for four or five years . In 1796 their third son, Edmund

died at the age of six . This was a heavy blow to Sarah who began suffering

from a nervous disorder from which she never recovered. Crabbe, a devoted

husband, tended her with exemplary care until her death in 1813. Robert

Southey, writing about Crabbe to his friend, Neville White, in 1808, said

"It was not long before his wife became deranged, and when all this was

told me by one who knew him well, five years ago, he was still almost confined

in his own house, anxiously waiting upon this wife in her long and hopeless

malady. A sad history! It is no wonder that he gives so melancholy a picture of

human life."

During

his time at Glemham, Crabbe composed several novels, none of which was

published. After Glemham, Crabbe moved to the village of Rendham in Suffolk,

where he stayed until 1805. His poem The Parish Register was all but completed

while at Rendham, and The Borough was also begun. 1805 was the last year of

Crabbe's stay in Suffolk, and it was made memorable in literature by the

appearance of the Lay of the Last Minstrel by Walter Scott. Crabbe first saw it

in a bookseller's shop in Ipswich, read it nearly through while standing at the

counter, and pronounced that a new and great poet had appeared. In October

1805, Crabbe returned with his wife and two sons to the parsonage at Muston. He

had been absent for nearly 13 years, of which four had been spent at Parham,

five at Great Glemham, and four at Rendham.

In

September 1807, Crabbe published a new volume of poems. Included in this volume

were The Library, The Newspaper, and The Village; the principal new poem was

The Parish Register, to which were added Sir Eustace Grey and The Hall of

Justice. The volume was dedicated to Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland,

nephew and sometime ward of Charles James Fox. An interval of 22 years had

passed since Crabbe's last appearance as an author, and he explained in the

preface to this volume the reasons for this lapse as being his higher calling

as a clergyman and his slow progress in poetical ability. This volume led to

Crabbe's general acceptance as an important poet. Four editions were issued

during the following year and a half, the fourth appearing in March 1809. The

reviews were unanimous in approval, headed by Francis Jeffrey in the Edinburgh

Review.

In

1809 Crabbe sent a copy of his poems in their fourth edition to Walter Scott,

who acknowledged them in a friendly reply. Scott told Crabbe "how for more

than twenty years he had desired the pleasure of a personal introduction to

him, and how, as a lad of eighteen, he had met with selections from The Village

and The Library in The Annual Register." This exchange of letters led to a

friendship that lasted for the rest of their lives, both authors dying in 1832.

Crabbe's favourite among Scott's "Waverley" novels was The Heart of

Midlothian.

The

success of The Parish Register in 1807 encouraged Crabbe to proceed with a far

longer poem, which he had been working on for several years. The Borough was

begun at Rendham in Suffolk in 1801, continued at Muston after his return in

1805, and finally completed during a long visit to Aldeburgh in the autumn of

1809. It was published in 1810. In spite of its defects, The Borough was an

outright success. The poem appeared in February 1810, and went through six

editions in the next six years.

When

he visited London a few years later and was received with general welcome in

the literary world, he was very surprised. "In my own village", he

told James Smith, " they think nothing of me." The three years

following the publication of The Borough were especially lonely for him. He did

have his two sons, George and John, with him; they had both passed through

Cambridge, one at Trinity and the other at Caius, and were now clergymen

themselves, each holding a curacy in the neighbourhood, enabling them to live

under the parental roof, but Mrs. Crabbe's health was now very poor, and Crabbe

had no daughter or female relative at home to help him with her care.

Later

life

Crabbe's

next volume of poetry, Tales, was published in the summer of 1812. It received

a warm welcome from the poet's admirers, was favourably reviewed by Jeffrey in

the Edinburgh Review and is considered to be his masterpiece. In the summer of

1813, Mrs. Crabbe felt well enough to want to see London again, and the father

and mother and two sons spent nearly three months in rooms in a hotel. Crabbe

was able to visit Dudley North and some of his other old friends, and to visit

and help the poor and distressed, remembering his own want and misery in the

great city thirty years earlier. The family returned to Muston in September,

and Mrs. Crabbe died at the end of October at the age of 63. Within days of his

wife's death Crabbe fell seriously ill, and was in danger of dying. He rallied,

however, and returned to the duties of his parish. In 1814, he became rector of

St James', the parish church of the town of Trowbridge in Wiltshire, a position

given to him by the new Duke of Rutland. He remained at Trowbridge for the rest

of his life.

His

two sons followed him, as soon as their existing engagements allowed them to

leave Leicestershire. The younger, John, who married in 1816, became his

father's curate, and the elder, who married a year later, became curate at

Pucklechurch, not far away. Crabbe's reputation as a poet continued to grow in

these years. His reputation soon made him a welcome guest in many houses to

which his position as rector might not have admitted him. Nearby at Bremhill

was the poet William Lisle Bowles, who introduced Crabbe to the noble family at

Bowood House, home of the Marquess of Lansdowne, who was always ready to

welcome those distinguished in literature and the arts. It was at Bowood that

Crabbe first met the poet Samuel Rogers, who became a close friend and had an

influence on Crabbe's poetry. In 1817, on the recommendation of Rogers, Crabbe

stayed in London from the middle of June to the end of July in order to enjoy

the literary society of the capital. While there he met Thomas Campbell, and

through him and Rogers was introduced to his future publisher John Murray.

In

June 1819, Crabbe published his collection Tales of the Hall. The last 13 years

of Crabbe's life were spent at Trowbridge, varied by occasional visits among

his friends at Bath and the surrounding neighbourhood, and by yearly visits to

his friend Samuel Hoare Jr in Hampstead. From there it was easy to visit his

literary friends in London, while William Wordsworth, Southey, and others

occasionally stayed with the family. Around 1820 Crabbe began suffering from

frequent severe attacks of neuralgia, and this illness, together with his age,

made him less and less able to travel to London.

In

the spring of 1822, Crabbe met Walter Scott for the first time in London, and

promised to visit him in Scotland in the autumn. He kept this promise during

George IV's visit to Edinburgh, in the course of which the King met Scott and

the poet was given a wine glass from which the King had drunk. Scott returned

from the meeting with the King to find Crabbe at his home. As John Gibson

Lockhart related in his Life of Sir Walter Scott,

Scott

entered the room that had been set aside for Crabbe, wet and hurried, and

embraced Crabbe with brotherly affection. The royal gift was forgotten—the

ample skirt of the coat within which it had been packed, and which he had

hitherto held cautiously in front of his person, slipped back to its more usual

position—he sat down beside Crabbe, and the glass was crushed to atoms. His

scream and gesture made his wife conclude that he had sat down on a pair of

scissors, or the like: but very little harm had been done except the breaking

of the glass.

Later

in 1822, Crabbe was invited to spend Christmas at Belvoir Castle, but was

unable to make the trip because of the winter weather. While at home, he

continued to write a large amount of poetry, leaving 21 manuscript volumes at

his death. A selection from these formed the Posthumous Poems, published in

1834. Crabbe continued to visit at Hampstead throughout the 1820s, often

meeting the writer Joanna Baillie and her sister Agnes. In the autumn of 1831,

Crabbe visited the Hoares. He left them in November, expressing his pain and

sadness at leaving in a letter, feeling that it might be the last time he saw

them. He left Clifton in November, and went direct to his son George, at

Pucklechurch. He was able to preach twice for his son, who congratulated him on

the power of his voice, and other encouraging signs of strength. "I will

venture a good sum, sir," he said, "that you will be assisting me ten

years hence." "Ten weeks" was Crabbe's answer, and the

prediction was right almost to the day.

After

a short time at Pucklechurch, Crabbe returned to his home at Trowbridge. Early

in January he reported continued drowsiness, which he felt was a sign of

increasing weakness. Later in the month he was prostrated by a severe cold.

Other complications arose, and it soon became apparent that he would not live

much longer. He died on 3 February 1832, with his two sons and his faithful

nurse by his side.

Poetry

Crabbe

grew up in the then-impoverished seacoast village of Aldeburgh, where his

father was collector of salt duties, and he was apprenticed to a surgeon at 14.

Hating his mean surroundings and unsuccessful occupation, he abandoned both in

1780 and went to London. In 1781 he wrote a desperate letter of appeal to

Edmund Burke, who read Crabbe’s writings and persuaded James Dodsley to publish

one of his didactic, descriptive poems, The Library (1781). Burke also used his

influence to have Crabbe accepted for ordination, and in 1782 he became

chaplain to the duke of Rutland at Belvoir Castle.

In

1783 Crabbe demonstrated his full powers as a poet with The Village. Written in

part as a protest against Oliver Goldsmith’s The Deserted Village (1770), which

Crabbe thought too sentimental and idyllic, the poem was his attempt to portray

realistically the misery and degradation of rural poverty. Crabbe made good use

in The Village of his detailed observation of life in the bleak countryside

from which he himself came. The Village was popular but was followed by an

unworthy successor, The Newspaper (1785), and after that Crabbe published no

poetry for the next 22 years. He did continue to write, contributing to John

Nichols’s The History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester (1795–1815)

and other works of local history; he also wrote a treatise on botany and three

novels, all of which he later burned.

Crabbe

married in 1783. His wife, Sarah, gave birth to seven children as they moved

through a succession of parishes; five died in infancy, and Sarah was affected

by mental illness from the late 1790s until her death in 1813. In 1807 Crabbe

began to publish poetry again. He reprinted his poems, together with a new

work, The Parish Register, a poem of more than 2,000 lines in which he made use

of a register of births, deaths, and marriages to create a compassionate

depiction of the life of a rural community. Other works followed, including The

Borough (1810), another long poem; Tales in Verse (1812); and Tales of the Hall

(1819).

Crabbe

is often called the last of the Augustan poets because he followed John Dryden,

Alexander Pope, and Samuel Johnson in using the heroic couplet, which he came

to handle with great skill. Like the Romantics, who esteemed his work, he was a

rebel against the realms of genteel fancy that poets of his day were forced to

inhabit, and he pleaded for the poet’s right to describe the commonplace

realities and miseries of human life. Another Aldeburgh resident, Benjamin

Britten, based his opera Peter Grimes (1945) on one of Crabbe’s grim verse

tales in The Borough.

Crabbe's

poetry was predominantly in the form of heroic couplets,[65] and has been

described as unsentimental in its depiction of provincial life and society.

John Wilson wrote that "Crabbe is confessedly the most original and vivid

painter of the vast varieties of common life that England has ever

produced;" and that "In all the poetry of this extraordinary man, we

see a constant display of the passions as they are excited and exacerbated by the

customs, laws, and institutions of society." The Cambridge History of

English Literature saw Crabbe's importance to be more in his influence than in

his works themselves: "He gave the poetry of nature new worlds to conquer

(rather than conquered them himself) by showing that the world of plain fact

and common detail may be material for poetry".

Although

Augustan literature played an important role in Crabbe's life and poetical

career, his body of work is unique and difficult to classify. His best works

are an original achievement in a new realistic poetical form. The major factor

in Crabbe's evolving from the Augustan influence to his use of realistic

narrative was the changing readership of the late 18th–early 19th century. In

the mid-18th century, literature was confined to the aristocratic and highly

educated class; with the rise of the middle class at the turn of the 19th

century, which came with a growing number of provincial papers, the heightening

in production of books in weekly instalments, and the establishment of

circulating libraries, the need for literature was spread throughout the middle

class.

Narrative

poetry was not a generally accepted mode in Augustan literature, making the

narrative form of Crabbe's mature works an innovation. This was due to some

extent to the rise in popularity of the novel in the late 18th–early 19th

century. Another innovation is the attention that Crabbe pays to details, both

in description and characterization. Augustan critics had espoused the view

that minute details should be avoided in favour of generality. Crabbe also

broke with Augustan tradition by not dealing with exalted and aristocratic

characters, but rather choosing people from middle and working-class society.

Poor characters like Crabbe's often anthologized "Peter Grimes" from

The Borough would have been completely unacceptable to Augustan critics. In

this way, Crabbe created a new way of presenting life and society in poetry.

Criticism

Wordsworth

predicted that Crabbe's poetry would last "from its combined merits as

truth and poetry fully as long as anything that has been expressed in verse

since it first made its appearance", though on another occasion, according

to Henry Crabb Robinson, he "blamed Crabbe for his unpoetical mode of

considering human nature and society." This latter opinion was also held

by William Hazlitt, who complained that Crabbe's characters "remind one of

anatomical preservations; or may be said to bear the same relation to actual

life that a stuffed cat in a glass-case does to the real one purring on the

hearth." Byron, besides what he said in English Bards and Scotch

Reviewers, declared, in 1816, that he considered Crabbe and Coleridge "the

first of these times in point of power and genius." Byron had felt that

English poetry had been steadily on the decline since the depreciation of Pope,

and pointed to Crabbe as the last remaining hope of a degenerate age.

Other

admirers included Jane Austen, Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Sir Walter Scott, who

used numerous quotes from Crabbe's poems in his novels. During Scott's final

illness, Crabbe was the last writer he asked to have read to him. Lord Byron

admired Crabbe's poetry, and called him "nature's sternest painter, yet

the best". According to critic Frank Whitehead, "Crabbe, in his verse

tales in particular, is an important—indeed, a major—poet whose work has been

and still is seriously undervalued." His early poems, which were

non-narrative essays in poetical form, gained him the approval of literary men

like Samuel Johnson, followed by a period of 20 years in which he wrote much,

destroying most of it, and published nothing. In 1807, he published his volume

Poems which started off the new realistic narrative method that characterised

his poetry for the rest of his career. Whitehead states that this narrative

poetry, which occupies the bulk of Crabbe's output, should be at the centre of

modern critical attention.

Q.

D. Leavis said of Crabbe: "He is (or ought to be—for who reads him?) a

living classic." His classic status was also supported by T. S. Eliot in

an essay on the poetry of Samuel Johnson in which Eliot grouped Crabbe together

favourably with Johnson, Pope and several other poets. Eliot said that "to

have the virtues of good prose is the first and minimum requirement of good

poetry." Critic Arthur Pollard believes that Crabbe definitely met this

qualification. Critic William Caldwell Roscoe, answering William Hazlitt's

question of why Crabbe had not in fact written prose rather than verse said

"have you ever read Crabbe's prose? Look at his letters, especially the

later ones, look at the correct but lifeless expression of his dedications and

prefaces—then look at his verse, and you will see how much he has exceeded 'the

minimum requirement of good poetry'." The critic F. L. Lucas summed up

Crabbe's qualities: "naïve, yet shrewd; straightforward, yet sardonic;

blunt, yet tender; quiet, yet passionate; realistic, yet romantic."

Crabbe, who is seen as a complicated poet, has been and often still is

dismissed as too narrow in his interests and in his way of responding to them

in his poetry. "At the same time as the critic is making such judgments,

he is all too often aware that Crabbe, nonetheless, defies

classification", says Pollard.

Pollard

has attempted to examine the negative views of Crabbe and the reasons for

limited readership since his lifetime: "Why did Crabbe's 'realism' and his

discovery of what in effect was the short story in verse fail to appeal to the

fiction-dominated Victorian age? Or is it that somehow psychological analysis

and poetry are uneasy bedfellows? But then why did Browning succeed and Crabbe

descend to the doldrums or to the coteries of admiring enthusiasts? And why

have we in this century [the 20th century] failed to get much nearer to him?

Does this mean that each succeeding generation must struggle to find his

characteristic and essential worth? FitzGerald was only one of many among those

who would make 'cullings from' or 'readings in' Crabbe. The implications of

such selection are clearly that, though much has vanished, much deserves to

remain."

Entomology

Crabbe

was known as a coleopterist and recorder of beetles, and is credited for

discovering the first specimen of Calosoma sycophanta L. to be recorded from

Suffolk. He published an essay on the Natural History of the Vale of Belvoir in

John Nichols's, Bibliotheca Topographia Britannica, VIII, Antiquities in

Leicestershire, 1790. It includes a very extensive list of local coleopterans,

and references more than 70 species.

Bibliography

Inebriety

(published 1775)

The

Candidate (published 1780)

The

Library (published 1781)

The

Village (published 1782)

The

Newspaper (published 1785)

Poems

(published 1807)

The

Borough (published 1810)

Tales

in Verse (published 1812)[85]

Tales

of the Hall (published 1819)

Posthumous

Tales (published 1834)

New

Poems by George Crabbe (published 1960)

Complete

Poetical Works (published 1988)

The

Voluntary Insane (published 1995)

Adaptations

Benjamin

Britten's opera Peter Grimes is based on The Borough. Britten also set an

extract from The Borough as the third of his Five Flower Songs, Op. 47.]

Charles Lamb's verse play The Wife's Trial; or, The Intruding Widow, written in

1827 and published the following year in Blackwood's Magazine, was based on

Crabbe's tale "The Confidant".

George

Crabbe Poems

A

Marriage Ring Late Wisdom Meeting The Borough. Letter XXII: Peter GrimesThe

Village (book 2)The Village: Book I

George

Crabbe Poems1.The Village: Book IThe Village Life, and every care that reigns

O'er

youthful peasants and declining swains;

What

labour yields, and what, that labour past,

Age,

in its hour of languor, finds at last;

Poem2.The

Borough. Letter Xxii: Peter GrimesOld Peter Grimes made fishing his employ,

His

wife he cabin'd with him and his boy,

And

seem'd that life laborious to enjoy:

To

town came quiet Peter with his fish,

Poem3.A

Marriage Ring

Poem4.The

Village (Book 2)Argument

There

are found amid the Evils of a Laborious Life, some Views of Tranquillity and

Happiness. - The Repose and Pleasure of a Summer Sabbath: interrupted by

Intoxication and Dispute. - Village Detraction. - Complaints of the Squire. -

The Evening Riots. - Justice. - Reasons for this unpleasant View of Rustic

Life: the Effect it should have upon the Lower Classes; and the Higher. - These

last have their peculiar Distresses: Exemplified in the Life and heroic Death

of Lord Robert Manners. - Concluding Address to his Grace the Duke of Rutland.

Poem5.MeetingMY

Damon was the first to wake

The gentle flame that cannot die;

My

Damon is the last to take

The faithful bosom's softest sigh:

Poem6.The

Borough. Letter I'DESCRIBE the Borough'--though our idle tribe

May

love description, can we so describe,

That

you shall fairly streets and buildings trace,

Poem7.The

Hall Of JusticeTake, take away thy barbarous hand,

And

let me to thy Master speak;

Poem8.The

Birth Of FlatteryMuse of my Spenser, who so well could sing

The

passions all, their bearings and their ties;

Who

could in view those shadowy beings bring,

Poem9.The

MournerYes! there are real mourners - I have seen

A

fair, sad girl, mild, suffering, and serene;

Attention

(through the day) her duties claim'd,

Poem10.The

Parish Register - Part I: BaptismsThe year revolves, and I again explore

The

simple Annals of my Parish poor;

What

Infant-members in my flock appear,

Poem11.The

Poor Of The Borough. Letter Xxi: Abel KeeneA QUIET, simple man was Abel Keene,

He

meant no harm, nor did he often mean;

He

kept a school of loud rebellious boys,

Poem12.The

Parish Register - Part Ii: MarriagesDISPOSED to wed, e'en while you hasten,

stay;

There's

great advantage in a small delay:

Thus

Ovid sang, and much the wise approve

Poem13.Sir

Eustace GreyI'll know no more;--the heart is torn

By

views of woe we cannot heal;

Long

shall I see these things forlorn,

Poem14.Late

WisdomWE'VE trod the maze of error round,

Long wandering in the winding glade;

And

now the torch of truth is found,

It only shows us where we strayed:

Poem15.The

CandidateYe idler things, that soothed my hours of care,

Where

would ye wander, triflers, tell me where?

Poem16.The

Borough. Letter Xv: Inhabitants Of The Alms-House. CleliaWE had a sprightly

nymph--in every town

Are

some such sprights, who wander up and down;

She

had her useful arts, and could contrive,

Poem17.Tale

XivA serious Toyman in the city dwelt,

Who

much concern for his religion felt;

Poem18.Tale

XiiiA Vicar died and left his Daughter poor -

It

hurt her not, she was not rich before:

...Read

Poem19.The Borough. Letter Xvii: The Hospital AndGovenors

AN

ardent spirit dwells with Christian love,

The

eagle's vigour in the pitying dove;

'Tis

not enough that we with sorrow sigh,

Poem20.The

Borough. Letter Ii: The Church'WHAT is a Church?'--Let Truth and Reason speak,

They

would reply, 'The faithful, pure, and meek;

From

Christian folds, the one selected race,

The

Best Poem Of George CrabbeThe Village: Book I

The

Village Life, and every care that reigns

O'er

youthful peasants and declining swains;

What

labour yields, and what, that labour past,

Age,

in its hour of languor, finds at last;

What

form the real picture of the poor,

Demand

a song--the Muse can give no more.

Fled

are those times, when, in harmonious strains,

The

rustic poet praised his native plains:

No

shepherds now, in smooth alternate verse,

Their

country's beauty or their nymphs' rehearse;

Yet

still for these we frame the tender strain,

Still

in our lays fond Corydons complain,

And

shepherds' boys their amorous pains reveal,

The

only pains, alas! they never feel.

On

Mincio's banks, in Caesar's bounteous reign,

If Tityrus found the Golden Age again,

Must sleepy bards the flattering dream prolong,

Mechanic echoes of the Mantuan song?

From Truth and Nature shall we widely stray,

Where Virgil, not where Fancy, leads the way?

Yes, thus the Muses sing of happy swains,

Because the Muses never knew their pains:

They boast their peasants' pipes; but peasants now

Resign their pipes and plod behind the plough;

And few, amid the rural-tribe, have time

To number syllables, and play with rhyme;

Save honest Duck, what son of verse could share

The poet's rapture , and the peasant's care?

Or the great labours of the field degrade,

With the new peril of a poorer trade ?

From this chief cause these idle praises spring,

That themes so easy few forbear to sing ;

For no deep thought the trifling subjects ask;

To sing of shepherds is an easy task:

The happy youth assumes the common strain,

A nymph his mistress, and himself a swain;

With no sad scenes he clouds his tuneful prayer

But all, to look like her, is painted fair.

I grant indeed that fields and flocks have charms

For him that grazes or for him that farms;

But when amid such pleasing scenes I trace

The poor laborious natives of the place,

And see the mid-day sun, with fervid ray,

On their bare heads and dewy temples play;

While some with feebler heads and fainter hearts,

Deplore their fortune, yet sustain their parts:

Then shall I dare these real ills to hide

In tinsel trappings of poetic pride ?

No; cast by Fortune on a frowning coast,

Which neither groves nor happy valleys boast ;

Where other cares than those the Muse relates,

And other shepherds dwell with other mates;

By such examples taught, I paint the Cot,

As Truth will paint it, and as Bards will not:

Nor you, ye poor, of letter'd scorn complain,

To you the smoothest song is smooth in vain;

O'ercome by labour, and bow'd down by time,

Feel you the barren flattery of a rhyme?

Can poets soothe you, when you pine for bread,

By winding myrtles round your ruin'd shed?

Can their light tales your weighty griefs o'erpower

Or glad with airy mirth the toilsome hour?

Lo! where the heath, with withering brake grown o'er,

Lends the light turf that warms the neighbouring

poor;

From thence a length of burning sand appears,

Where the thin harvest waves its wither'd ears;

Rank weeds, that every art and care defy,

Reign o'er the land, and rob the blighted rye:

There thistles stretch their prickly arms afar,

And to the ragged infant threaten war;

There poppies nodding, mock the hope of toil;

There the blue bugloss paints the sterile soil;

Hardy and high, above the slender sheaf,

The slimy mallow waves her silky leaf;

O'er the young shoot the charlock throws a shade,

And clasping tares cling round the sickly blade;

With mingled tints the rocky coasts abound,

And a sad splendour vainly shines around.

So looks the nymph whom wretched arts adorn,

Betray'd by man, then left for man to scorn;

Whose cheek in vain assumes the mimic rose ,

While her sad eyes the troubled breast disclose ;

Whose outward splendour is but folly's dress ,

Exposing most, when most it gilds distress .

Here joyous roam a wild amphibious race,

With sullen woe display'd in every face;

Who, far from civil arts and social fly,

And scowl at strangers with suspicious eye.

Here too the lawless merchant of the main

Draws from his plough th' intoxicated swain;

Want only claim'd the labour of the day,

But vice now steals his nightly rest away.

Where are the swains, who, daily labour done ,

With rural games play'd down the setting sun;

Who struck with matchless force the bounding ball ,

Or made the pond'rous quoit obliquely fall;

While some huge Ajax, terrible and strong,

Engaged some artful stripling of the throng,

And fell beneath him, foil'd, while far around

Hoarse triumph rose, and rocks return'd the sound?

Where now are these?--Beneath yon cliff they stand,

To show the freighted pinnace where to land;

To load the ready steed with guilty haste,

To fly in terror o'er the pathless waste,

Or, when detected, in their straggling course,

To foil their foes by cunning or by force;

Or, yielding part (which equal knaves demand),

To gain a lawless passport through the land .

Here, wand'ring long amid these frowning fields,

I sought the simple life that Nature yields;

Rapine and Wrong and Fear usurp'd her place,

And a bold, artful, surly, savage race;

Who, only skill'd to take the finny tribe,

The yearly dinner, or septennial bribe,

Wait on the shore, and, as the waves run high,

On the tost vessel bend their eager eye,

Which to their coast directs its vent'rous way ;

Theirs, or the ocean's , miserable prey.

As on their neighbouring beach yon swallows stand,

And wait for favouring winds to leave the land;

While still for flight the ready wing is spread:

So waited I the favouring hour, and fled;

Fled from those shores where guilt and famine reign,

And cried, Ah! hapless they who still remain;

Who still remain to hear the ocean roar ,

Whose greedy waves devour the lessening shore ;

Till some fierce tide, with more imperious sway,

Sweeps the low hut and all it holds away;

When the sad tenant weeps from door to door,

And begs a poor protection from the poor!

But these are scenes where Nature's niggard hand

Gave a spare portion to the famish'd land;

Hers is the fault, if here mankind complain

Of fruitless toil and labour spent in vain;

But yet in other scenes more fair in view,

Where Plenty smiles--alas! she smiles for few

And those who taste not, yet behold her store,

Are as the slaves that dig the golden ore,

The wealth around them makes them doubly poor.

Or will you deem them amply paid in health,

Labour's fair child, that languishes with wealth?

Go then! and see them rising with the sun,

Through a long course of daily toil to run;

See them beneath the dog-star's raging heat,

When the knees tremble and the temples beat;

Behold them, leaning on their scythes, look o'er

The labour past, and toils to come explore;

See them alternate suns and showers engage,

And hoard up aches and anguish for their age;

Through fens and marshy moors their steps pursue,

When their warm pores imbibe the evening dew;

Then own that labour may as fatal be

To these thy slaves, as thine excess to thee.

Amid this tribe too oft a manly pride

Strives in strong toil the fainting heart to hide;

There may you see the youth of slender frame

Contend with weakness, weariness, and shame:

Yet, urged along, and proudly loth to yield,

He strives to join his fellows of the field.

Till long-contending nature droops at last,

Declining health rejects his poor repast,

His cheerless spouse the coming danger sees,

And mutual murmurs urge the slow disease.

Yet grant them health, 'tis not for us to tell,

Though the head droops not, that the heart is well;

Or will you praise that homely, healthy fare,

Plenteous and plain, that happy peasants share!

Oh! trifle not with wants you cannot feel,

Nor mock the misery of a stinted meal;

Homely, not wholesome, plain, not plenteous, such

As you who praise would never deign to touch .

Ye gentle souls, who dream of rural ease,

Whom the smooth stream and smoother sonnet please;

Go! if the peaceful cot your praises share,

Go look within, and ask if peace be there;

If peace be his--that drooping weary sire,

Or theirs, that offspring round their feeble fire;

Or hers, that matron pale, whose trembling hand

Turns on the wretched hearth th' expiring brand!

Nor yet can Time itself obtain for these

Life's latest comforts, due respect and ease;

For yonder see that hoary swain, whose age

Can with no cares except his own engage;

Who, propp'd on that rude staff, looks up to see

The bare arms broken from the withering tree,

On which, a boy, he climb'd the loftiest bough,

Then his first joy, but his sad emblem now.

He once was chief in all the rustic trade;

His steady hand the straightest furrow made;

Full many a prize he won, and still is proud

To find the triumphs of his youth allow'd;

A transient pleasure sparkles in his eyes,

He hears and smiles, then thinks again and sighs:

For now he journeys to his grave in pain;

The rich disdain him; nay, the poor disdain;

Alternate masters now their slave command,

Urge the weak efforts of his feeble hand,

And, when his age attempts its task in vain,

With ruthless taunts, of lazy poor complain.

Oft may you see him, when he tends the sheep,

His winter-charge, beneath the hillock weep;

Oft hear him murmur to the winds that blow

O'er his white locks and bury them in snow,

When, roused by rage and muttering in the morn,

He mends the broken hedge with icy thorn:--

"Why do I live, when I desire to be

At once from life and life's long labour free?

Like leaves in spring, the young are blown away,

Without the sorrows of a slow decay;

I, like yon wither'd leaf, remain behind,

Nipp'd by the frost, and shivering in the wind;

There it abides till younger buds come on,

As I, now all my fellow-swains are gone;

Then, from the rising generation thrust,

It falls, like me, unnoticed to the dust.

"These fruitful fields, these numerous flocks I

see,

Are others' gain , but killing cares to me;

To me the children of my youth are lords,

Cool in their looks, but hasty in their words:

Wants of their own demand their care; and who

Feels his own want and succours others too?

A lonely, wretched man, in pain I go,

None need my help, and none relieve my woe;

Then let my bones beneath the turf be laid,

And men forget the wretch they would not aid."

Thus groan the old, till, by disease oppress'd,

They taste a final woe, and then they rest.

Theirs is yon house that holds the parish-poor,

Whose walls of mud scarce bear the broken door ;

There, where the putrid vapours, flagging, play,

And the dull wheel hums doleful through the day;--

There children dwell who know no parents' care;

Parents, who know no children's love, dwell there!

Heart-broken matrons on their joyless bed,

Forsaken wives , and mothers never wed;

Dejected widows with unheeded tears,

And crippled age with more than childhood fears;

The lame, the blind, and, far the happiest they!

The moping idiot and the madman gay .

Here too the sick their final doom receive,

Here brought, amid the scenes of grief, to grieve,

Where the loud groans from some sad chamber flow,

Mix'd with the clamours of the crowd below;

Here, sorrowing, they each kindred sorrow scan,

And the cold charities of man to man:

Whose laws indeed for ruin'd age provide ,

And strong compulsion plucks the scrap from pride;

But still that scrap is bought with many a sigh,

And pride embitters what it can't deny.

Say ye, oppress'd by some fantastic woes,

Some jarring nerve that baffles your repose;

Who press the downy couch, while slaves advance

With timid eye, to read the distant glance;

Who with sad prayers the weary doctor tease,

To name the nameless ever-new disease;

Who with mock patience dire complaints endure,

Which real pain and that alone can cure;

How would ye bear in real pain to lie ,

Despised, neglected, left alone to die?

How would ye bear to draw your latest breath ,

Where all that's wretched paves the way for death?

Such is that room which one rude beam divides ,

And naked rafters form the sloping sides;

Where the vile bands that bind the thatch are seen,

And lath and mud are all that lie between;

Save one dull pane, that, coarsely patch'd, gives way

To the rude tempest, yet excludes the day:

Here, on a matted flock, with dust o'erspread,

The drooping wretch reclines his languid head;

For him no hand the cordial cup applies,

Or wipes the tear that stagnates in his eyes;

No friends with soft discourse his pain beguile,

Or promise hope till sickness wears a smile.

But soon a loud and hasty summons calls,

Shakes the thin roof, and echoes round the walls;

Anon, a figure enters, quaintly neat,

All pride and business, bustle and conceit;

With looks unalter'd by these scenes of woe,

With speed that, entering, speaks his haste to go,

He bids the gazing throng around him fly,

And carries fate and physic in his eye :

A potent quack, long versed in human ills,

Who first insults the victim whom he kills;

Whose murd'rous hand a drowsy Bench protect ,

And whose most tender mercy is neglect.

Paid by the parish for attendance here,

He wears contempt upon his sapient sneer;

In haste he seeks the bed where Misery lies,

Impatience mark'd in his averted eyes;

And, some habitual queries hurried o'er,

Without reply, he rushes on the door:

His drooping patient, long inured to pain,

And long unheeded, knows remonstrance vain;

He ceases now the feeble help to crave

Of man; and silent sinks into the grave .

But ere his death some pious doubts arise,

Some simple fears, which "bold bad" men

despise;

Fain would he ask the parish-priest to prove

His title certain to the joys above:

For this he sends the murmuring nurse, who calls

The holy stranger to these dismal walls:

And doth not he, the pious man, appear,

He, " passing rich with forty pounds a year "?

Ah! No ; a shepherd of a different stock,

And far unlike him, feeds this little flock:

A jovial youth, who thinks his Sunday's task

As much as God or man can fairly ask;

The rest he gives to loves and labours light,

To fields the morning, and to feasts the night;

None better skill'd the noisy pack to guide,

To urge their chase, to cheer them or to chide;

A sportsman keen, he shoots through half the day,

And, skill'd at whist, devotes the night to play:

Then, while such honours bloom around his head,

Shall he sit sadly by the sick man's bed ,

To raise the hope he feels not, or with zeal

To combat fears that e'en the pious feel?

Now once again the gloomy scene explore,

Less gloomy now; the bitter hour is o'er,

The man of many sorrows sighs no more.--

Up yonder hill, behold how sadly slow

The bier moves winding from the vale below;

There lie the happy dead, from trouble free,

And the glad parish pays the frugal fee:

No more, O Death! thy victim starts to hear

Churchwarden stern , or kingly overseer;

No more the farmer claims his humble bow,

Thou art his lord, the best of tyrants thou!

Now to the church behold the mourners come,

Sedately torpid and devoutly dumb;

The village children now their games suspend,

To see the bier that bears their ancient friend;

For he was one in all their idle sport,

And like a monarch ruled their little court.

The pliant bow he form'd, the flying ball,

The bat, the wicket , were his labours all;

Him now they follow to his grave, and stand

Silent and sad, and gazing, hand in hand;

While bending low, their eager eyes explore

The mingled relics of the parish poor;

The bell tolls late, the moping owl flies round,

Fear marks the flight and magnifies the sound;

The busy priest, detain'd by weightier care,

Defers his duty till the day of prayer;

And, waiting long, the crowd retire distress'd,

To think a poor man's bones should lie unbless'd.