232-] English Literature

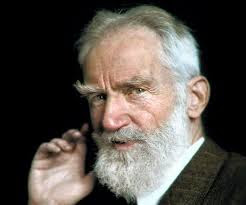

George Bernard Shaw

Stage success: 1900–1914

During

the first decade of the twentieth century, Shaw secured a firm reputation as a

playwright. In 1904 J. E. Vedrenne and Harley Granville-Barker established a

company at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square, Chelsea to present modern

drama. Over the next five years they staged fourteen of Shaw's plays. The

first, John Bull's Other Island, a comedy about an Englishman in Ireland,

attracted leading politicians and was seen by Edward VII, who laughed so much

that he broke his chair. The play was withheld from Dublin's Abbey Theatre, for

fear of the affront it might provoke, although it was shown at the city's Royal

Theatre in November 1907. Shaw later wrote that William Butler Yeats, who had

requested the play, "got rather more than he bargained for ... It was

uncongenial to the whole spirit of the neo-Gaelic movement, which is bent on

creating a new Ireland after its own ideal, whereas my play is a very

uncompromising presentment of the real old Ireland." Nonetheless, Shaw and

Yeats were close friends; Yeats and Lady Gregory tried unsuccessfully to

persuade Shaw to take up the vacant co-directorship of the Abbey Theatre after

J. M. Synge's death in 1909. Shaw admired other figures in the Irish Literary

Revival, including George Russell and James Joyce, and was a close friend of

Seán O'Casey, who was inspired to become a playwright after reading John Bull's

Other Island.

Man

and Superman, completed in 1902, was a success both at the Royal Court in 1905

and in Robert Loraine's New York production in the same year. Among the other

Shaw works presented by Vedrenne and Granville-Barker were Major Barbara

(1905), depicting the contrasting morality of arms manufacturers and the

Salvation Army; The Doctor's Dilemma (1906), a mostly serious piece about

professional ethics; and Caesar and Cleopatra, Shaw's counterblast to

Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, seen in New York in 1906 and in London the

following year.

Now

prosperous and established, Shaw experimented with unorthodox theatrical forms

described by his biographer Stanley Weintraub as "discussion drama"

and "serious farce". These plays included Getting Married (premiered

1908), The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (1909), Misalliance (1910), and Fanny's

First Play (1911). Blanco Posnet was banned on religious grounds by the Lord

Chamberlain (the official theatre censor in England), and was produced instead

in Dublin; it filled the Abbey Theatre to capacity. Fanny's First Play, a

comedy about suffragettes, had the longest initial run of any Shaw play—622

performances.

Androcles

and the Lion (1912), a less heretical study of true and false religious

attitudes than Blanco Posnet, ran for eight weeks in September and October

1913. It was followed by one of Shaw's most successful plays, Pygmalion,

written in 1912 and staged in Vienna the following year, and in Berlin shortly

afterwards. Shaw commented, "It is the custom of the English press when a

play of mine is produced, to inform the world that it is not a play—that it is

dull, blasphemous, unpopular, and financially unsuccessful. ... Hence arose an

urgent demand on the part of the managers of Vienna and Berlin that I should

have my plays performed by them first." The British production opened in

April 1914, starring Sir Herbert Tree and Mrs Patrick Campbell as,

respectively, a professor of phonetics and a cockney flower-girl. There had

earlier been a romantic liaison between Shaw and Campbell that caused Charlotte

Shaw considerable concern, but by the time of the London premiere it had ended.

The play attracted capacity audiences until July, when Tree insisted on going

on holiday, and the production closed. His co-star then toured with the piece

in the US.

Fabian years: 1900–1913

In

1899, when the Boer War began, Shaw wished the Fabians to take a neutral stance

on what he deemed, like Home Rule, to be a "non-Socialist" issue.

Others, including the future Labour prime minister Ramsay MacDonald, wanted

unequivocal opposition, and resigned from the society when it followed Shaw. In

the Fabians' war manifesto, Fabianism and the Empire (1900), Shaw declared that

"until the Federation of the World becomes an accomplished fact we must

accept the most responsible Imperial federations available as a substitute for

it".

As

the new century began, Shaw became increasingly disillusioned by the limited

impact of the Fabians on national politics. Thus, although a nominated Fabian

delegate, he did not attend the London conference at the Memorial Hall,

Farringdon Street in February 1900, that created the Labour Representation

Committee—precursor of the modern Labour Party. By 1903, when his term as

borough councillor expired, he had lost his earlier enthusiasm, writing:

"After six years of Borough Councilling I am convinced that the borough

councils should be abolished". Nevertheless, in 1904 he stood in the

London County Council elections. After an eccentric campaign, which Holroyd

characterises as "[making] absolutely certain of not getting in", he

was duly defeated. It was Shaw's final foray into electoral politics.

Nationally, the 1906 general election produced a huge Liberal majority and an

intake of 29 Labour members. Shaw viewed this outcome with scepticism; he had a

low opinion of the new prime minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, and saw

the Labour members as inconsequential: "I apologise to the Universe for my

connection with such a body".

In

the years after the 1906 election, Shaw felt that the Fabians needed fresh

leadership, and saw this in the form of his fellow-writer H. G. Wells, who had

joined the society in February 1903. Wells's ideas for reform—particularly his

proposals for closer cooperation with the Independent Labour Party—placed him

at odds with the society's "Old Gang", led by Shaw. According to

Cole, Wells "had minimal capacity for putting [his ideas] across in public

meetings against Shaw's trained and practised virtuosity". In Shaw's view,

"the Old Gang did not extinguish Mr Wells, he annihilated himself". Wells

resigned from the society in September 1908; Shaw remained a member, but left

the executive in April 1911. He later wondered whether the Old Gang should have

given way to Wells some years earlier: "God only knows whether the Society

had not better have done it". Although less active—he blamed his advancing

years—Shaw remained a Fabian.

In

1912 Shaw invested £1,000 for a one-fifth share in the Webbs' new publishing

venture, a socialist weekly magazine called The New Statesman, which appeared

in April 1913. He became a founding director, publicist, and in due course a

contributor, mostly anonymously. He was soon at odds with the magazine's

editor, Clifford Sharp, who by 1916 was rejecting his contributions—"the

only paper in the world that refuses to print anything by me", according

to Shaw.

First World War

After

the First World War began in August 1914, Shaw produced his tract Common Sense

About the War, which argued that the warring nations were equally culpable.

Such a view was anathema in an atmosphere of fervent patriotism, and offended

many of Shaw's friends; Ervine records that "is appearance at any public

function caused the instant departure of many of those present."

Despite

his errant reputation, Shaw's propagandist skills were recognised by the

British authorities, and early in 1917 he was invited by Field Marshal Haig to

visit the Western Front battlefields. Shaw's 10,000-word report, which

emphasised the human aspects of the soldier's life, was well received, and he

became less of a lone voice. In April 1917 he joined the national consensus in

welcoming America's entry into the war: "a first class moral asset to the

common cause against junkerism".

Three

short plays by Shaw were premiered during the war. The Inca of Perusalem,

written in 1915, encountered problems with the censor for burlesquing not only

the enemy but the British military command; it was performed in 1916 at the

Birmingham Repertory Theatre. O'Flaherty V.C., satirising the government's

attitude to Irish recruits, was banned in the UK and was presented at a Royal

Flying Corps base in Belgium in 1917. Augustus Does His Bit, a genial farce,

was granted a licence; it opened at the Royal Court in January 1917.

Ireland

Shaw

had long supported the principle of Irish Home Rule within the British Empire

(which he thought should become the British Commonwealth). In April 1916 he

wrote scathingly in The New York Times about militant Irish nationalism:

"In point of learning nothing and forgetting nothing these fellow-patriots

of mine leave the Bourbons nowhere." Total independence, he asserted, was

impractical; alliance with a bigger power (preferably England) was essential.

The Dublin Easter Rising later that month took him by surprise. After its

suppression by British forces, he expressed horror at the summary execution of

the rebel leaders, but continued to believe in some form of Anglo-Irish union.

In How to Settle the Irish Question (1917), he envisaged a federal arrangement,

with national and imperial parliaments. Holroyd records that by this time the

separatist party Sinn Féin was in the ascendency, and Shaw's and other moderate

schemes were forgotten.

In

the postwar period, Shaw despaired of the British government's coercive

policies towards Ireland, and joined his fellow-writers Hilaire Belloc and G.

K. Chesterton in publicly condemning these actions. The Anglo-Irish Treaty of

December 1921 led to the partition of Ireland between north and south, a

provision that dismayed Shaw. In 1922 civil war broke out in the south between

its pro-treaty and anti-treaty factions, the former of whom had established the

Irish Free State. Shaw visited Dublin in August, and met Michael Collins, then

head of the Free State's Provisional Government. Shaw was much impressed by

Collins, and was saddened when, three days later, the Irish leader was ambushed

and killed by anti-treaty forces. In a letter to Collins's sister, Shaw wrote:

"I met Michael for the first and last time on Saturday last, and am very

glad I did. I rejoice in his memory, and will not be so disloyal to it as to

snivel over his valiant death". Shaw remained a British subject all his

life, but took dual British-Irish nationality in 1934.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)