271-] English Literature

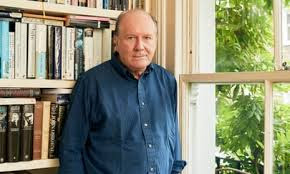

William Boyd

Interview With William Boyd

QTHE WHITE REVIEW — How do you go about writing? Have you always written in the same way?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Yes, I have actually. I’m part of that pre-computer generation and I’ve

always written in longhand. All my novels have manuscripts, which is rare for

anybody under the age of forty. I used to write my first draft in my tiny anal

retentive handwriting and then I’d write a fair copy in large legible

handwriting. I would then give that second draft to a typing agency – that

dates me – and the typists typed it up from my fair copy so that I could then

hand it in to the publisher. I’ve always had this process of writing a draft

and then writing it all again, however long it takes. Now, of course, I type

the second draft onto a screen.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — How much changes between drafts?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — I change things all the time. When you are copying a sentence or typing

it or rewriting it you think, ‘Oh, this is clumsy’, or ‘I can stick that word

here’, so the difference from manuscript to typescript or manuscript to fair

copy is often huge. It’s a very good editorial process and I wonder if writers

who write directly onto a screen lose that. Of course, you rewrite and polish

anyway, but there’s something about the two forms, there’s a real moment of

decision, and just making that transfer, I wouldn’t change that working method

now. I do write screenplays straight onto the screen, I do write journalism

straight onto the screen, but I would never write a novel or a short story like

that, I just seem to need the two forms – the handwritten and then the

perfection of type.

The last few months of my working life have

been very simple: I get up in the morning and write the novel. I can write for

about three hours and then I’m knackered but I can type up what I’ve written.

I’ve been doing that seven days a week. I’ve been writing my latest novel since

the early summer of last year and since December I’ve been working full-time

seven days a week on it. I’m now polishing it and tweaking it but I’m already

thinking about the next one and that makes me relaxed because that plane is

circling and waiting to be called in to land.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — Do you have a structure worked out when you sit down to write?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Yes. It takes me about three years to write a novel and I spend roughly

two years figuring it out and one year writing it. Iris Murdoch, who worked in

the same way, called it the period of invention and the period of composition.

I think that’s quite a neat division. It’s become absolutely rigid for me now.

I get an idea for a novel, which is usually

one sentence or a concept. Then I spend a long time thinking about it, filling

out notebooks, travelling, acquiring the library I need for the book. I set

about making more and more elaborate plans for the narrative and making lots

and lots of mistakes, going up blind alleys and developing characters or

sub-themes that fizzle out. Even then, I haven’t actually started writing the

book. That whole period of invention is absolutely crucial in my work.

Eventually, and usually when I know how the book is going to end, I will write

a draft of the last paragraph or the last few lines – so I’m that sure of it –

and only at that stage do I write chapter one and start the book.

Then

it takes me about nine months or a year to write it but I write with confidence

– not particularly fast but with fluency because I’m not stopping to think,

‘What happens next?’ I’ve already made all those mistakes and all of those bad

decisions and corrected them. Of course, I still get lots of new ideas as I’m

writing but there’s a real template, or as I describe it a skeleton, and then I

add the flesh when I write it.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — Do you play around with the voice of your characters in the

invention period?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Yes, because those elements are the first questions you ask yourself

once you’ve got your idea and the whole process of invention is a series of

questions and answers that goes on over this period of two years. For example,

I ask myself whether it is going to be in the first person or the third person,

and that decision is absolutely crucial. Am I going to write from one point of

view or from many points of view? Is my central character going to be male or female?

The answer to these questions trigger a whole set of other questions: ‘Oh, it’s

a woman, right, OK, how old is she? What’s her name? How tall is she?’ And so

on and so forth and this aggregate of information begins to accrue and you see

stories and storylines emerging.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — What are you currently working on?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — It’s a novel that starts in Vienna in 1913 and it’s about a young

Englishman who is an actor. He’s got a sexual dysfunction and he’s engaged to

be married, so he decides to go out to Vienna to try out this new-fangled

psychoanalysis lark to see if it can cure him of this particular problem. He

starts being psychoanalysed and he meets another woman there and then, because

it’s one my novels, things go from bad to worse and World War One begins.

It’s

very long and it’s possibly one of my most complex plots ever because he gets

embroiled in all sorts of Buchanesque adventures, but it’s got a lot more sex

in it than John Buchan ever had. It covers a lot of ground but I now realise,

two weeks before I hand it in to my editor, that it’s actually about lying and

uncertainty which seems to me to be a very modern state of mind. And with

Vienna in 1913-1914, we are at the beginning of the modern era and in the

capital of a decadent empire. Something about the city then made it the focus

and locus of what was modern.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — How do you go about researching your novels? Do you read a lot?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Yes, I often read novels set in the period I want to write about. For

this latest novel, for example, I read Joseph Roth and Robert Musil. I find

novels very useful because what a novelist saw in 1912 or 1913 is not necessary

what a historian writing today will see. I also use photographs a lot. I’ve

never really gone beyond the twentieth century – 1902 is as early a novel as I

have set – so photographic evidence exists and I find books of photographs

fantastically helpful. Then I use all sorts of newspapers, magazines, guide

books – but all contemporary.

It’s not about reading some book on the

Viennese Secession, it’s about reading books that are much more banal because

as a novelist the banal is what you are looking for. What struck Joseph Roth as

he described a country scene in The Radetzky March is what I want to reproduce

through the eyes of this young Englishman in Vienna for the first time. It’s a

very selective process and if you get the detail right suddenly that world

comes alive. As you sift through this material you find that you are not

looking at it in the way that a journalist or a historian would look at it –

you are looking at it for something that intrigues and seems unusual.

Take

the business of communicating for example: you could make telephone calls in

1914-15 but only 20,000 people had telephones. The telegram and the telegraph

offices were the main avenues for communication because you just popped one in

the post at half a pence a word. These details make the book come alive but

they have to be fed in seamlessly so that it doesn’t look like a gobbet of

research. We’ve all read novels where you plough through three pages on the

manufacture of rubber and you realise that the writer has been to Singapore to

see a rubber plantation and by God are we going to hear about it. It is a very

interesting process to make it seem entirely natural and yet at the same time

you want the reader to be aware of time travel.

I

always quote something from Ulysses where Bloom goes into a pub in Dublin and

orders a glass of claret and a sardine sandwich. That seems very modern and it

brings a Dublin pub to life in a way that knowing that Guinness costs one and

sixpence doesn’t. Language is another thing. People swore as violently in 1913

as they do today, maybe not in mixed company but amongst men, and certainly

soldiers’ language was as rich as anyone’s.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — Where do you find traces of that? Because it doesn’t appear much

in the literature of the time…

AWILLIAM

BOYD — It does if you know where to look for it. I can give you two good

examples. If you read the letters of James Joyce to Nora Barnacle, 1909 or

thereabouts, they are the most sexually candid letters you can find two lovers

writing to each other. Joyce was in Trieste and Nora was in Dublin so they

wrote each other some dirty letters for sexual stimulation at a distance.

The other one is a novel by Frederic Manning

which might be the best novel that came out of World War One. Manning wrote two

versions of the book: one called Middle Parts of Fortune which is unexpurgated

and another called Her Privates We which had no swearwords in it and was

published at the time. Manning was an intellectual who fought at the battle of

the Somme as a private soldier. The soldiers he writes about are all saying

‘Fuck’ and ‘Cunt’ like a soldier today would, but of course our image of the

Tommy is of a plucky chap with a fag in his mouth saying, ‘Cor, blimey, it’s

the Huns throwing over’.

This

is what is so fantastic about Manning’s novel. You realise the soldiers didn’t

give a toss about the war, they hated their officers, they hated the officers

back home, and the only things they wanted were food, drink, and sex if it was

available. These words weren’t invented in 1940. You just need to read

Shakespeare’s soldiers to see that it’s an absolute truth, but gentility has tended

to mask that so it does take some unearthing.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — What was the genesis of your forthcoming novel on

psychoanalysis?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — I became very interested in psychoanalysis, which is one of the three

great scientific revolutions. There is the Copernican revolution, when we

realised that the sun didn’t go around us but that we went around the sun.

There’s the Darwinian revolution – we are animals – and then there’s the

Freudian revolution – half the time we don’t know why we do things because our

unconscious mind is at work.

Whatever anyone may think of Freud and however

discredited he is, there is no doubt that we are all Freudians. Even though the

unconscious existed before Freud, he schematised and systematised it and

changed the way we think about ourselves. So to begin with I asked myself,

‘What would it have been like to be psychoanalysed and to realise that half the

things you do are driven by forces that you are only partially aware of?’ Then

I decided I’d send my protagonist off to Vienna before the First World War when

psychoanalysis was new and controversial, and off I went.

That

was the idea that grabbed me and it’s nearly always like that. I start off with

an idea and it has enough mass in it to be a four-hundred or five-hundred page

novel. The ideas I get for short stories or movies or a piece I might write are

different. There is a certain category of idea I get which is gravid enough or

has enough potential to fill a novel. I’ve never written a short novel.

Some

people like to start and see where they end up, but I’m not that kind of

writer. I like to know my destination and my period of composition is not

fraught with having to stop and invent, which is where novels get abandoned of

course. The first sixty pages come like that and then you think, ‘What does she

do next?’ I’ve never abandoned a novel because I never get to that stage.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — Some writers say that once they start writing their characters

take on a life of their own and become uncontrollable.

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Vladimir Nabokov was always asked this and he was very much

anti-Freudian and anti the unconscious. He said: ‘All my characters are galley

slaves and I’m the man on the deck with the whip’. I feel rather like that

because I try to make my characters live and breathe on the page as real and

complex human beings. You are the master of that particular world and they are

your creatures. Sometimes you don’t know where you get ideas from but it’s not

the character taking over. That’s a romantic fallacy or convention – the

inspired driven artist at the mercy of his or her muse. I think writing a novel

takes so long that there is something very dogged and methodical about it. I

believe in the Flaubertian-Joycean model of the artist controlling everything, not

the drink-fuelled spontaneity of the muse descending.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — How does that relate to when you are writing about characters

who are already iconic figures such as Woolf, Picasso, Hemingway or Joyce? How

do you create their voice?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — They are usually people I have been very intrigued by anyway and I’ve

read a great deal about them. It’s a kind of thought experiment. I think, ‘What

would it actually be like to meet Virginia Woolf?’ I’ve never particularly

liked Virginia Woolf and I’ve read everything and taught her books for many

years but she just seems to me an unpleasant, snobbish, slightly bogus person.

I know she was disturbed as well and that’s how I imagined her.

If you read her letters and diaries, you see

what type of person she is – we’ve all met them. The challenge as a writer is

to bring that iconic figure alive in a way that makes them a real person rather

than a postcard that you bought at the National Portrait Gallery. I’ve written

stories about Chekhov, Wittgenstein, Brahms and Cyril Connolly, people I’m

really intrigued by, and I try to make them live as characters in fiction. It’s

about stripping away the myth and getting to the real person, but they are

always people about whom I have been curious about and read a lot about. I

can’t imagine writing a novel about George VI for example.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — The Duke of Windsor is much more interesting.

AWILLIAM

BOYD — Yes, and that is the wonderful thing about writing fiction. I got Logan

Mountstuart to meet all these people that I was intrigued by so I could present

them through his eyes. Some people who knew the Duke and Duchess of Windsor who

I have spoken to have said that their appearance in Any Human Heart is a

fascinating and very credible portrait of them. Some of my favourite short

stories of mine are these biographical short stories because when it is

successful I feel like I captured the essence of the person in those fifteen or

twenty pages and the reader gets a sense of them as a character quite apart from

their reputation.

QTHE

WHITE REVIEW — Does this tie in with your interest in blurring the lines

between fact and fiction? Say with Nat Tate for example? Or is it really just a

narrative device you are using?

AWILLIAM

BOYD — That exercise was to make something utterly fictitious seem completely

real so that the line is blurred, so that your suspension of disbelief is

rocky, and it’s amazing how it could be done with tricks and presentation. And

why did I do it? If you look at three books where I do this, The New

Confessions, Nat Tate and Any Human Heart – published between 1987 and 2002, so

that’s a long time – I think they stand up as a trilogy of books all exploring

the same thing: is it true or is it false?

There is an ongoing argument that somehow

non-fiction is more powerful and gripping than fiction and I felt that I wanted

to reclaim the top of the hill for fiction. These three books were a series of

attempts to prove that something made-up could supplant what you might regard

as real.