236- ] English Literature

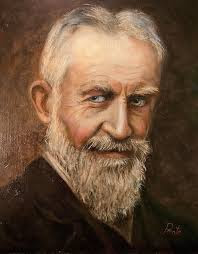

George Bernard Shaw

List of works by George Bernard Shaw

The

following is a list of works by George Bernard Shaw. The first section shows

works in chronological sequence as written, the second tabulates these works by

genre. In addition to the works listed here, Shaw produced a large quantity of

journalism and criticism, particularly in his role as a music and theatre

critic. These items are not included in the lists, except for the collections which

Shaw himself supervised and which were published during his lifetime; these

appear in the brief third section. Other collections of Shaw's journalism and

correspondence, and editions of his plays, have been published since his death

but again are not listed here.

The

main source is the chronology provided by the International Shaw Society. Items

not covered by the chronology are separately cited. Items marked are works

published anonymously by or for the Fabian Society, where Shaw's authorship was

later confirmed by the Society. Except where indicated, the publication year is

that of first publication.

Chronological list

|

Date written Title Year first performed (plays) Year of publication |

1878 The Legg

Papers (abandoned draft of novel) unpublished |

1878 "My

Dear Dorothea..." 1906 |

|

1878 Passion

Play (fragment) 1971 |

1879 Immaturity

(novel) 1930 |

1880 The

Irrational Knot (novel) serial 1885–7; book 1905 |

|

1881 Love

Among the Artists (novel) serial 1887–8; book 1900 |

1882 Cashel

Byron's Profession (novel) serial 1885–6; book 1886; rev 1889,

1901 |

1883 An

Unsocial Socialist (novel) serial 1884; book 1887 |

|

1884 "A

Manifesto" (Fabian tract 2) 1884 |

1884 Un Petit

Drame (playlet) 1959 |

1884–92 Widowers'

Houses (play) 1893 1893; rev. 1898 |

|

1885 "The

Miraculous Revenge" (short story) 1906 |

1885 To

provident landlords and capitalists (Fabian tract 3) 1885 |

1887 The true

radical programme (Fabian tract 6: Shaw a contributor) 1887 |

|

1887–88 An

Unfinished Novel (novel fragment) 1958 |

1889 Fabian

Essays in Socialism (ed. Shaw with 2 Shaw essays) 1889; rev.

1908, 1931, 1948 |

1890 What

socialism is (Fabian tract 13)‡ 1890 |

|

1890 "Ibsen"

(Lecture before the Fabian Society) 1970 |

1891 The

Quintessence of Ibsenism (criticism) 1891;

rev. 1913 |

1892 Fabian

election manifesto (Fabian tract 40)‡ 1892[3] |

|

1892 The

Fabian Society: what it has done, and how it has done it (Fabian tract

42)1892 rev. 1899 |

1892 "Vote!

Vote!! Vote!!!" (Fabian Tract 43) 1892 |

1893 The

Impossibilities of Anarchism (Fabian tract 45) 1892 |

|

1893 The

Philanderer (play) 1905 1898 |

1893 Mrs.

Warren's Profession (play) 1902 1898, rev. 1930 |

1893–94 Arms

and the Man (play) 1894 1898, rev. 1930 |

|

1894 A Plan

of Campaign for Labor (incorporating "To Your Tents, O Israel")

(Fabian tract 49)‡ 1894 |

1894 Candida

(play) 1897 1898, rev. 1930 |

1895 The Man

of Destiny (play) 1897 1898, rev. 1930 |

|

1895 The

Sanity of Art (art criticism) 1895, rev. 1908 |

1895–96 You

Never Can Tell (play) 1899 1898, rev. 1930 |

1896 Fabian

report and resolutions to the IS and TU Congress (Fabian tract 70)‡ 1896 |

|

1896 The

Devil's Disciple (play) 1897 1901, rev. 1904 |

1898 The

Perfect Wagnerite (music criticism) 1898, rev. 1907 |

1898 Caesar

and Cleopatra (play) 1901 1901, rev. 1930 |

|

1899 Captain

Brassbound's Conversion (play) 1900 1901 |

1900 Fabianism

and The Empire: A Manifesto (ed. Shaw) 1900 |

1900 Women as

councillors (Fabian tract 93)‡ 1900[3] |

|

1901 Socialism

for millionaires (Fabian tract 107) 1901 |

1901 The

Admirable Bashville (play) 1902 1901 |

1901–02 Man

and Superman incorporating Don Juan in Hell (play) 1905 1903; rev.

1930 |

|

1904 Fabianism

and the fiscal question (Fabian tract 116) 1904 |

1904 John

Bull's Other Island (play) 1904 1907; rev. 1930 |

1904 How He

Lied to Her Husband (play) 1904 1907 |

|

1904 The

Common Sense of Municipal Trading (social commentary) 1908 |

1905 Major

Barbara (play) 1905 1907; rev. 1930, 1945 |

1905 Passion,

Poison, and Petrifaction (play) 1905 1905 |

|

1906 The

Doctor's Dilemma (play) 1906 1911 |

1907 The

Interlude at the Playhouse (playlet) 1907 1927 |

1907–08 Getting

Married (play) 1908 1911 |

|

1907–08 Brieux:

A Preface (criticism) 1910 |

1909 The

Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet (play) 1909 1911; rev. 1930 |

1909 Press

Cuttings (play) 1909 1909 |

|

1909 The

Glimpse of Reality (play) 1927 1926 |

1909 The

Fascinating Foundling (play) 1928 1926 |

1909 Misalliance

(play) 1910 1914; rev. 1930 |

|

1910 Socialism

and superior brains: a reply to Mr. Mallock (Fabian tract 146) 1926[4] |

1910 The Dark

Lady of the Sonnets (play) 1910 1914 |

1910–11 Fanny's

First Play (play) 1911 1914; |

|

1912 Androcles

and the Lion (play) 1913 1916 |

1912 Overruled

(play) 1912 1916 |

1912 Pygmalion 1913 1916;

rev. 1941 |

|

1913 Beauty's

Duty (playlet) 1932 |

1913 Great

Catherine: Whom Glory Still Adores (play) 1913 1919 |

1913–14 The

Music-Cure (play) 1914 1926 |

|

1914 Common

Sense about The War (political commentary) 1914 |

1914 The Case

for Belgium (pamphlet) 1914[5] |

1915 The Inca

of Perusalem (play) 1916 1919 |

|

1915 O'Flaherty

V.C. (play) 1917 1919 |

1915 More

Common Sense about The War (political commentary) unpublished |

1916 Augustus

Does His Bit (play) 1917 1919 |

|

1916–17 Heartbreak

House (play) 1920 1919 |

1917 Doctors’

Delusions; Crude Criminology; Sham Education (compilation) 1931 |

1917 Annajanska,

the Bolshevik Empress (play) 1918 1919 |

|

1917 How To

Settle The Irish Question (political commentary) 1917 |

1917 What I

Really Wrote about The War (political commentary) 1931 |

1918–20 Back

to Methuselah (play) 1922 1921; rev. 1930, 1945 |

|

1919 Peace

Conference Hints (political commentary) 1919 |

1919 Ruskin's

Politics (lecture of 21 November 1919) 1921 |

1920–21 Jitta's

Atonement (play, adapted from the German) 1923 1926 |

|

1923 Saint

Joan (play) 1923 1924 |

1925 Imprisonment

(social commentary) 1925;

rev. 1946 as The Crime of Imprisonment |

1928 The

Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and Capitalism 1928; rev. 1937 |

|

1928 The

Apple Cart (play) 1929 1930 |

1929 The

League of Nations (political commentary) 1929 |

1930 Socialism:

Principles and Outlook, and Fabianism (Fabian tract 233) 1929 |

|

1931 Pen

Portraits and Reviews (criticism) 1931 |

1931–34 The

Millionairess (play) 1936 1936 |

1932 The

Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (story) 1932 |

|

1932 Essays

in Fabian Socialism (reprinted tracts with 2 new essays) 1932 |

1932 The

Rationalization of Russia (political commentary) 1964 |

1933 The

Future of Political Science in America (political commentary) 1933 |

|

1933 Village

Wooing (play) 1934 1934 |

1933 On The

Rocks (play) 1933 1934 |

1934 The

Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles (play) 1935 1936 |

|

1934 The Six

of Calais (play) 1934 1936 |

1934 Short

Stories, Scraps, and Shavings (stories & playlets) 1934 1934 |

1936 Arthur

and the Acetone (playlet) 1936 1936 |

|

1936 Cymbeline

Refinished (play) 1937 1938 |

1936 Geneva

(play) 1938 1939; rev. 1939, 1940, 1946, 1947 |

1936–47 Buoyant

Billions (play) 1948 1949 |

|

1937–38 Pygmalion

(film screenplay, with co-writers) 1938 1941 |

1938–39 In

Good King Charles's Golden Days (play) 1939 1939; rev. 1947 |

1939 Shaw

Gives Himself Away: An Autobiographical Miscellany 1939 |

|

1944 Everybody’s

Political What's What (political commentary) 1944 |

1948 Farfetched

Fables (play) 1950 1951 |

1948 The RADA

Graduates' Keeepsake and Counsellor (RADA handbook) 1948 |

|

1949 Sixteen

Self Sketches (revision of Shaw Gives Himself Away) 1949 |

1949 Shakes

versus Shav (puppet play) 1949 1950 |

1950 Why She

Would Not (play) 1957 1960 |

|

1950 Rhyming

Picture Guide to Ayot Saint Lawrence 1950 |

Works listed by genre |

|

Dramatic works

|

Date written |

Title |

Year first performed |

|

Year of publication |

|

|

|

1878 |

Passion Play: A Dramatic Fragment |

unperformed |

|

|

|

|

|

1884 |

Un Petit Drame |

unperformed |

|

|

|

|

|

1884–92 |

Widowers' Houses |

1893 |

|

1893; rev. 1898 |

|

|

|

1893 |

The Philanderer |

1905 |

|

1898 |

|

|

|

1893 |

Mrs. Warren's Profession |

1902 |

|

1898, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1893–94 |

Arms and the Man |

1894 |

|

1898, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1894 |

Candida |

1897 |

|

1898, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1895 |

The Man of Destiny |

1897 |

|

1898, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1895–96 |

You Never Can Tell |

1899 |

|

1898, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1896 |

The Devil's Disciple |

1897 |

|

1901, rev. 1904 |

|

|

|

1898 |

Caesar and Cleopatra |

1901 |

|

1901, rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1899 |

Captain Brassbound's Conversion |

1900 |

|

1901 |

|

|

|

1901 |

The Admirable Bashville |

1902 |

|

1901 |

|

|

|

1901–02 |

Man and Superman incorporating Don Juan in Hell |

1905 |

|

1930 |

|

|

|

1904 |

John Bull's Other Island |

1904 |

|

1907; rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1904 |

How He Lied to Her Husband |

1904 |

|

1907 |

|

|

|

1905 |

Major Barbara (play) |

1905 |

|

1907; rev. 1930, 1945 |

|

|

|

1905 |

Passion, Poison, and Petrifaction |

1905 |

|

1905 |

|

|

|

1906 |

The Doctor's Dilemma |

1906 |

|

1911 |

|

|

|

1907 |

The Interlude at the Playhouse (playlet) |

1907 |

|

1927 |

|

|

|

1907–08 |

Getting Married |

1908 |

|

1911 |

|

|

|

1909 |

The Shewing-Up of Blanco Posnet |

1909 |

|

1911; rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1909 |

Press Cuttings |

1909 |

|

1909 |

|

|

|

1909 |

The Glimpse of Reality |

1927 |

|

1926 |

|

|

|

1909 |

The Fascinating Foundling |

1928 |

|

1926 |

|

|

|

1909 |

Misalliance |

1910 |

|

1914; rev. 1930 |

|

|

|

1910 |

The Dark Lady of the Sonnets |

1910 |

|

1914 |

|

|

|

1910–11 |

Fanny's First Play |

1911 |

|

1914; |

|

|

|

1912 |

Androcles and the Lion |

1913 |

|

1916 |

|

|

|

1912 |

Overruled |

1912 |

|

1916 |

|

|

|

1912 |

Pygmalion |

1913 |

|

1916; rev. 1941 |

|

|

|

1913 |

Beauty's Duty (playlet) |

unperformed |

|

1932 |

|

|

|

1913 |

Great Catherine: Whom Glory Still Adores |

1913 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1913–14 |

The Music-Cure |

1914 |

|

1926 |

|

|

|

1915 |

The Inca of Perusalem |

1916 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1915 |

O'Flaherty V.C. |

1917 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1916 |

Augustus Does His Bit |

1917 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1916–17 |

Heartbreak House |

1920 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1917 |

Annajanska, the Bolshevik Empress |

1918 |

|

1919 |

|

|

|

1918–20 |

Back to Methuselah |

1922 |

|

1921; rev. 1930, 1945 |

|

|

|

1920–21 |

Jitta's Atonement (adapted from the German) |

1923 |

|

1926 |

|

|

|

1923 |

Saint Joan |

1923 |

|

1924 |

|

|

|

1928 |

The Apple Cart |

1929 |

|

1930 |

|

|

|

1931–34 |

The Millionairess |

1936 |

|

1936 |

|

|

|

1933 |

Village Wooing |

1934 |

|

1934 |

|

|

|

1933 |

On The Rocks |

1933 |

|

1934 |

|

|

|

1934 |

The Simpleton of the Unexpected Isles |

1935 |

|

1936 |

|

|

|

1934 |

The Six of Calais |

1934 |

|

1936 |

|

|

|

1936 |

Arthur and the Acetone (playlet) |

1936 |

|

1936 |

|

|

|

1936 |

Cymbeline Refinished |

1937 |

|

1938 |

|

|

|

1936 |

Geneva |

1938 |

|

1939; rev. 1939, 1940, 1946, 1947 |

|

|

|

1936–47 |

Buoyant Billions |

1948 |

|

1949 |

|

|

|

1937–38 |

Pygmalion (film screenplay, with co-writers) |

1938 |

|

1941 |

|

|

|

1938–39 |

In Good King Charles's Golden Days |

1939 |

|

1939; rev. 1947 |

|

|

|

1948 |

Farfetched Fables |

1950 |

|

1951 |

|

|

|

1949 |

Shakes versus Shav (puppet play) |

1949 |

|

1950 |

|

|

|

1950 |

Why She Would Not |

1957 |

|

1960 |

|

|

Political writings

|

Date written |

Title |

Year of publication |

|

1884 |

"A Manifesto" (Fabian tract 2) |

1884 |

|

1885 |

To provident landlords and capitalists (Fabian

tract 3) |

1885 |

|

1887 |

The true radical programme (Fabian tract 6: Shaw a

contributor) |

1887 |

|

1889 |

Fabian Essays in Socialism (ed. Shaw with 2 Shaw

essays) |

1889; rev. 1908, 1931, 1948 |

|

1890 |

What socialism is (Fabian tract 13) |

1890 |

|

1892 |

Fabian election manifesto (Fabian tract 40)‡ |

1892 |

|

1892 |

The Fabian Society: what it has done, and how it

has done it (Fabian tract 42) |

1892 rev. 1899 |

|

1892 |

"Vote! Vote!! Vote!!!" (Fabian Tract 43) |

1892 |

|

1893 |

The Impossibilities of Anarchism (Fabian tract 45) |

1892 |

|

1894 |

A Plan of Campaign for Labor (incorporating

"To Your Tents, O Israel") (Fabian tract 49) |

1894 |

|

1896 |

Fabian report and resolutions to the IS and TU

Congress (Fabian tract 70) |

1896 |

|

1900 |

Fabianism and The Empire: A Manifesto (ed. Shaw) |

1900 |

|

1900 |

Women as councillors (Fabian tract 93) |

1900 |

|

1901 |

Socialism for millionaires (Fabian tract 107) |

1901 |

|

1904 |

Fabianism and the fiscal question (Fabian tract

116) |

Fabian Tracts 1902–18 |

|

1904 |

The Common Sense of Municipal Trading (social

commentary) |

1908 |

|

1910 |

Socialism and superior brains: a reply to Mr.

Mallock (Fabian tract 146) |

1926 |

|

1914 |

Common Sense about The War (political commentary) |

1914 |

|

1914 |

The Case for Belgium (pamphlet) |

1914 |

|

1915 |

More Common Sense about The War (political

commentary) |

unpublished |

|

1917 |

How To Settle The Irish Question (political

commentary) |

1917 |

|

1917 |

What I Really Wrote about The War (political commentary) |

1931 |

|

1919 |

Peace Conference Hints (political commentary) |

1919 |

|

1919 |

Ruskin's Politics (lecture of 21 November 1919) |

1921 |

|

1925 |

Imprisonment (social commentary) |

1925; rev. 1946 as The Crime of Imprisonment |

|

1928 |

The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism and

Capitalism |

1928; rev. 1937 |

|

1929 |

The League of Nations (political commentary) |

1929 |

|

1930 |

Socialism: Principles and Outlook, and Fabianism

(Fabian tract 233) |

1929 |

|

1932 |

Essays in Fabian Socialism (reprinted tracts with 2

new essays) |

1932 |

|

1932 |

The Rationalization of Russia (political

commentary) |

1964 |

|

1933 |

The Future of Political Science in America

(political commentary) |

1933 |

|

1933 |

The Political Madhouse in America and Nearer Home

(lecture) |

1933 |

|

1944 |

Everybody’s Political What's What (political

commentary) |

1944 |

Fiction

|

Date written Title Year of publication |

1878 The Legg

Papers (abandoned draft of novel) unpublished |

1879 Immaturity

(novel) 1930 |

|

1880 The

Irrational Knot (novel) serial

1885–7; book 1905 |

1881 Love

Among the Artists (novel) serial

1887–8; book 1900 |

1882 Cashel

Byron's Profession (novel) serial

1885–6; book 1886; rev 1889, 1901 |

|

1883 An

Unsocial Socialist (novel) serial

1884; book 1887 |

1885 "The

Miraculous Revenge" (short story) 1906 |

1887–88 An

Unfinished Novel (novel fragment) 1958 |

|

1932 The

Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God (story) 1932 |

1934 Short

Stories, Scraps, and Shavings (stories & playlets) 1934 |

Criticism |

|

Date written Title Year of publication |

1895 The

Sanity of Art (art criticism) 1895,

rev. 1908 |

1898 The

Perfect Wagnerite (analysis, Wagner's Ring cycle) 1898, rev. 1907 |

|

1890 "Ibsen"

(Lecture before the Fabian Society) 1970 |

1891 The

Quintessence of Ibsenism (criticism) 1891;

rev. 1913 |

1907–08 Brieux:

A Preface (criticism) 1910 |

|

1931 Pen

Portraits and Reviews (criticism) 1931 |

Miscellaneous writings |

Date written Title Year of publication |

|

1878 "My

Dear Dorothea..." 1906 |

1939 Shaw

Gives Himself Away: An Autobiographical Miscellany 1939 |

1948 The RADA

Graduates' Keeepsake and Counsellor (RADA handbook) 1948[11] |

|

1949 Sixteen

Self Sketches (revision of Shaw Gives Himself Away) 1949 |

1950 Rhyming

Picture Guide to Ayot Saint Lawrence 1950 |

|

Collections published in Shaw's lifetime

|

Title |

Year of publication |

|

Plays Pleasant and Unpleasant: (Unpleasant:

Widowers' Houses, The Philanderer and Mrs. Warren's Profession. Pleasant:

Arms and the Man, Candida, The Man of Destiny, You Never Can Tell.) |

1898 |

|

Three Plays for Puritans ( The Devil's Disciple,

Caesar and Cleopatra, Captain Brassbound's Conversion) |

1901 |

|

Dramatic Opinions and Essays: (theatre criticism,

Saturday Review 1895-98) |

1906 |

|

Translations and Tomfooleries: (collection of short

plays, including Jitta's Atonement; The Admirable Bashville; Press Cuttings;

The Glimpse of Reality; Passion, Poison, and Petrification; The Fascinating

Foundling; The Music-Cure) |

1926 |

|

Our Theatres in the Nineties: (theatre criticism,

Saturday Review 1895-98) |

1932 |

|

Music In London: (music criticism, Star 1888–89;

World 1890-94) |

1937 |

.jpeg)