235- ] English Literature

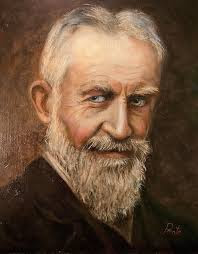

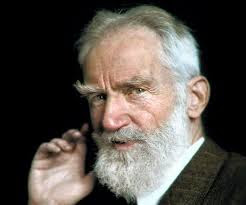

George Bernard Shaw

Beliefs and opinions

Throughout

his lifetime Shaw professed many beliefs, often contradictory. This

inconsistency was partly an intentional provocation—the Spanish

scholar-statesman Salvador de Madariaga describes Shaw as "a pole of

negative electricity set in a people of positive electricity". In one area

at least Shaw was constant: in his lifelong refusal to follow normal English forms

of spelling and punctuation. He favoured archaic spellings such as

"shew" for "show"; he dropped the "u" in words

like "honour" and "favour"; and wherever possible he

rejected the apostrophe in contractions such as "won't" or

"that's". In his will, Shaw ordered that, after some specified

legacies, his remaining assets were to form a trust to pay for fundamental

reform of the English alphabet into a phonetic version of forty letters. Though

Shaw's intentions were clear, his drafting was flawed, and the courts initially

ruled the intended trust void. A later out-of-court agreement provided a sum of

£8,300 for spelling reform; the bulk of his fortune went to the residuary

legatees—the British Museum, the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and the National

Gallery of Ireland. Most of the £8,300 went on a special phonetic edition of

Androcles and the Lion in the Shavian alphabet, published in 1962 to a largely

indifferent reception.

Shaw's

views on religion and Christianity were less consistent. Having in his youth

proclaimed himself an atheist, in middle age he explained this as a reaction

against the Old Testament image of a vengeful Jehovah. By the early twentieth

century, he termed himself a "mystic", although Gary Sloan, in an

essay on Shaw's beliefs, disputes his credentials as such. In 1913 Shaw

declared that he was not religious "in the sectarian sense", aligning

himself with Jesus as "a person of no religion". In the preface

(1915) to Androcles and the Lion, Shaw asks "Why not give Christianity a

chance?" contending that Britain's social order resulted from the

continuing choice of Barabbas over Christ. In a broadcast just before the

Second World War, Shaw invoked the Sermon on the Mount, "a very moving

exhortation, and it gives you one first-rate tip, which is to do good to those

who despitefully use you and persecute you". In his will, Shaw stated that

his "religious convictions and scientific views cannot at present be more

specifically defined than as those of a believer in creative revolution".

He requested that no one should imply that he accepted the beliefs of any

specific religious organisation, and that no memorial to him should "take

the form of a cross or any other instrument of torture or symbol of blood

sacrifice".

Shaw

espoused racial equality, and inter-marriage between people of different races.

Despite his expressed wish to be fair to Hitler, he called anti-Semitism

"the hatred of the lazy, ignorant fat-headed Gentile for the pertinacious

Jew who, schooled by adversity to use his brains to the utmost, outdoes him in

business".[304] In The Jewish Chronicle he wrote in 1932, "In every

country you can find rabid people who have a phobia against Jews, Jesuits,

Armenians, Negroes, Freemasons, Irishmen, or simply foreigners as such.

Political parties are not above exploiting these fears and jealousies."

In

1903 Shaw joined in a controversy about vaccination against smallpox. He called

vaccination "a peculiarly filthy piece of witchcraft"; in his view

immunisation campaigns were a cheap and inadequate substitute for a decent

programme of housing for the poor, which would, he declared, be the means of

eradicating smallpox and other infectious diseases. Less contentiously, Shaw

was keenly interested in transport; Laurence observed in 1992 a need for a

published study of Shaw's interest in "bicycling, motorbikes, automobiles,

and planes, climaxing in his joining the Interplanetary Society in his

nineties". Shaw published articles on travel, took photographs of his

journeys, and submitted notes to the Royal Automobile Club.

Shaw

strove throughout his adult life to be referred to as "Bernard Shaw"

rather than "George Bernard Shaw", but confused matters by continuing

to use his full initials—G.B.S.—as a by-line, and often signed himself "G.

Bernard Shaw". He left instructions in his will that his executor (the

Public Trustee) was to license publication of his works only under the name

Bernard Shaw. Shaw scholars including Ervine, Judith Evans, Holroyd, Laurence

and Weintraub, and many publishers have respected Shaw's preference, although

the Cambridge University Press was among the exceptions with its 1988 Cambridge

Companion to George Bernard Shaw.

Legacy and influence

Theatrical

Shaw

did not found a school of dramatists as such, but Crawford asserts that today

"we recognise [him] as second only to Shakespeare in the British

theatrical tradition ... the proponent of the theater of ideas" who struck

a death-blow to 19th-century melodrama. According to Laurence, Shaw pioneered

"intelligent" theatre, in which the audience was required to think,

thereby paving the way for the new breeds of twentieth-century playwrights from

Galsworthy to Pinter.

Crawford

lists numerous playwrights whose work owes something to that of Shaw. Among

those active in Shaw's lifetime he includes Noël Coward, who based his early

comedy The Young Idea on You Never Can Tell and continued to draw on the older

man's works in later plays. T. S. Eliot, by no means an admirer of Shaw,

admitted that the epilogue of Murder in the Cathedral, in which Becket's slayers

explain their actions to the audience, might have been influenced by Saint

Joan. The critic Eric Bentley comments that Eliot's later play The Confidential

Clerk "had all the earmarks of Shavianism ... without the merits of the

real Bernard Shaw". Among more recent British dramatists, Crawford marks

Tom Stoppard as "the most Shavian of contemporary playwrights";

Shaw's "serious farce" is continued in the works of Stoppard's

contemporaries Alan Ayckbourn, Henry Livings and Peter Nichols.

Shaw's

influence crossed the Atlantic at an early stage. Bernard Dukore notes that he

was successful as a dramatist in America ten years before achieving comparable

success in Britain. Among many American writers professing a direct debt to

Shaw, Eugene O'Neill became an admirer at the age of seventeen, after reading

The Quintessence of Ibsenism. Other Shaw-influenced American playwrights

mentioned by Dukore are Elmer Rice, for whom Shaw "opened doors, turned on

lights, and expanded horizons"; William Saroyan, who empathised with Shaw

as "the embattled individualist against the philistines"; and S. N.

Behrman, who was inspired to write for the theatre after attending a

performance of Caesar and Cleopatra: "I thought it would be agreeable to

write plays like that".

Assessing

Shaw's reputation in a 1976 critical study, T. F. Evans described Shaw as

unchallenged in his lifetime and since as the leading English-language

dramatist of the (twentieth) century, and as a master of prose style. The

following year, in a contrary assessment, the playwright John Osborne

castigated The Guardian's theatre critic Michael Billington for referring to

Shaw as "the greatest British dramatist since Shakespeare". Osborne

responded that Shaw "is the most fraudulent, inept writer of Victorian

melodramas ever to gull a timid critic or fool a dull public". Despite

this hostility, Crawford sees the influence of Shaw in some of Osborne's plays,

and concludes that though the latter's work is neither imitative nor

derivative, these affinities are sufficient to classify Osborne as an inheritor

of Shaw.

In

a 1983 study, R. J. Kaufmann suggests that Shaw was a key

forerunner—"godfather, if not actually finicky paterfamilias"—of the

Theatre of the Absurd. Two further aspects of Shaw's theatrical legacy are

noted by Crawford: his opposition to stage censorship, which was finally ended

in 1968, and his efforts which extended over many years to establish a National

Theatre. Shaw's short 1910 play The Dark Lady of the Sonnets, in which

Shakespeare pleads with Queen Elizabeth I for the endowment of a state theatre,

was part of this campaign.

Writing

in The New Statesman in 2012 Daniel Janes commented that Shaw's reputation had

declined by the time of his 150th anniversary in 2006 but had recovered

considerably. In Janes's view, the many current revivals of Shaw's major works

showed the playwright's "almost unlimited relevance to our times". In

the same year, Mark Lawson wrote in The Guardian that Shaw's moral concerns

engaged present-day audiences, and made him—like his model, Ibsen—one of the

most popular playwrights in contemporary British theatre.

The

Shaw Festival in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario, Canada is the second largest

repertory theatre company in North America. It produces plays by or written

during the lifetime of Shaw as well as some contemporary works. The Gingold

Theatrical Group, founded in 2006, presents works by Shaw and others in New

York City that feature the humanitarian ideals that his work promoted. It

became the first theatre group to present all of Shaw's stage work through its

monthly concert series Project Shaw.

General

In

the 1940s the author Harold Nicolson advised the National Trust not to accept

the bequest of Shaw's Corner, predicting that Shaw would be totally forgotten

within fifty years. In the event, Shaw's broad cultural legacy, embodied in the

widely used term "Shavian", has endured and is nurtured by Shaw

Societies in various parts of the world. The original society was founded in

London in 1941 and survives; it organises meetings and events, and publishes a

regular bulletin The Shavian. The Shaw Society of America began in June 1950;

it foundered in the 1970s but its journal, adopted by Penn State University

Press, continued to be published as Shaw: The Annual of Bernard Shaw Studies until

2004. A second American organisation, founded in 1951 as "The Bernard Shaw

Society", remains active as of 2016. More recent societies have been

established in Japan and India.

Besides

his collected music criticism, Shaw has left a varied musical legacy, not all

of it of his choosing. Despite his dislike of having his work adapted for the

musical theatre ("my plays set themselves to a verbal music of their

own") two of his plays were turned into musical comedies: Arms and the Man

was the basis of The Chocolate Soldier in 1908, with music by Oscar Straus, and

Pygmalion was adapted in 1956 as My Fair Lady with book and lyrics by Alan Jay

Lerner and music by Frederick Loewe. Although he had a high regard for Elgar,

Shaw turned down the composer's request for an opera libretto, but played a

major part in persuading the BBC to commission Elgar's Third Symphony, and was

the dedicatee of The Severn Suite (1930).

The

substance of Shaw's political legacy is uncertain. In 1921 Shaw's erstwhile

collaborator William Archer, in a letter to the playwright, wrote: "I

doubt if there is any case of a man so widely read, heard, seen, and known as

yourself, who has produced so little effect on his generation." Margaret

Cole, who considered Shaw the greatest writer of his age, professed never to

have understood him. She thought he worked "immensely hard" at

politics, but essentially, she surmises, it was for fun—"the fun of a

brilliant artist". After Shaw's death, Pearson wrote: "No one since

the time of Tom Paine has had so definite an influence on the social and

political life of his time and country as Bernard Shaw."

In

its obituary tribute to Shaw, The Times Literary Supplement concluded:

He

was no originator of ideas. He was an insatiable adopter and adapter, an

incomparable prestidigitator with the thoughts of the forerunners. Nietzsche,

Samuel Butler (Erewhon), Marx, Shelley, Blake, Dickens, William Morris, Ruskin,

Beethoven and Wagner all had their applications and misapplications. By bending

to their service all the faculties of a powerful mind, by inextinguishable wit,

and by every artifice of argument, he carried their thoughts as far as they

would reach—so far beyond their sources that they came to us with the vitality

of the newly created.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)