108- ] English Literature

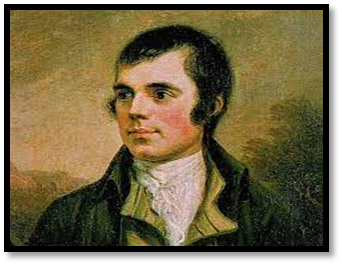

Robert Burns

Robert

Burns (born January 25, 1759, Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland—died July 21, 1796,

Dumfries, Dumfriesshire), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish

poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and

is celebrated worldwide, who wrote lyrics and songs in Scots and in English. He

was also famous for his amours and his rebellion against orthodox religion and

morality.. He is the best known of the poets who have written in the Scots

language, although much of his writing is in a "light Scots dialect"

of English, accessible to an audience beyond Scotland. He also wrote in

standard English, and in these writings his political or civil commentary is

often at its bluntest.

He

is regarded as a pioneer of the Romantic movement, and after his death he

became a great source of inspiration to the founders of both liberalism and

socialism, and a cultural icon in Scotland and among the Scottish diaspora

around the world. Celebration of his life and work became almost a national

charismatic cult during the 19th and 20th centuries, and his influence has long

been strong on Scottish literature. In 2009 he was chosen as the greatest Scot

by the Scottish public in a vote run by Scottish television channel STV.

As

well as making original compositions, Burns also collected folk songs from

across Scotland, often revising or adapting them. His poem (and song)

"Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the

year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial

national anthem of the country. Other poems and songs of Burns that remain well

known across the world today include "A Red, Red Rose", "A Man's

a Man for A' That", "To a Louse", "To a Mouse",

"The Battle of Sherramuir", "Tam o' Shanter" and "Ae

Fond Kiss".

Life

Robert

Burns was born in 1759, two miles (3 km) south of Ayr,in Alloway, Scotland, ,

the eldest of the seven children of William and Agnes Brown Burnes , tenant

farmer from Dunnottar in the Mearns, and Agnes Broun (1732–1820), the daughter

of a Kirkoswald tenant farmer.[3][4][5] . Like his father, Burns was a

self-educated tenant farmer. However, toward the end of his life he became an

excise collector in Dumfries, where he died in 1796.

He

was born in a house built by his father (now the Burns Cottage Museum), where

he lived until Easter 1766, when he was seven years old. William Burnes sold

the house and took the tenancy of the 70-acre (280,000 m2) Mount Oliphant farm,

southeast of Alloway. Here Burns grew up in poverty and hardship, and the

severe manual labour of the farm left its traces in a weakened constitution.[6]

Burns’s

father had come to Ayrshire from Kincardineshire in an endeavour to improve his

fortunes, but, though he worked immensely hard first on the farm of Mount

Oliphant, which he leased in 1766, and then on that of Lochlea, which he took

in 1777, ill luck dogged him, and he died in 1784, worn out and bankrupt. It

was watching his father being thus beaten down that helped to make Robert both

a rebel against the social order of his day and a bitter satirist of all forms

of religious and political thought that condoned or perpetuated inhumanity. He

received some formal schooling from a teacher as well as sporadically from

other sources. He acquired a superficial reading knowledge of French and a bare

smattering of Latin, and he read most of the important 18th-century English

writers as well as Shakespeare, Milton, and Dryden. His knowledge of Scottish

literature was confined in his childhood to orally transmitted folk songs and

folk tales together with a modernization of the late 15th-century poem

“Wallace.” His religion throughout his adult life seems to have been a

humanitarian Deism.

He

was given irregular schooling and a lot of his education was with his father,

who taught his children reading, writing, arithmetic, geography, and history

and also wrote for them A Manual of Christian Belief.[6] He was also taught and

tutored by the young teacher John Murdoch (1747–1824), who opened an

"adventure school" in Alloway in 1763 and taught Latin, French, and

mathematics to both Robert and his brother Gilbert (1760–1827) from 1765 to

1768 until Murdoch left the parish. After a few years of home education, Burns

was sent to Dalrymple Parish School in mid-1772 before returning at harvest

time to full-time farm labouring until 1773, when he was sent to lodge with

Murdoch for three weeks to study grammar, French, and Latin.

By

the age of 15, Burns was the principal labourer at Mount Oliphant. During the

harvest of 1774, he was assisted by Nelly Kilpatrick (1759–1820), who inspired

his first attempt at poetry, "O, Once I Lov'd A Bonnie Lass". In

1775, he was sent to finish his education with a tutor at Kirkoswald, where he met

Peggy Thompson (born 1762), to whom he wrote two songs, "Now Westlin'

Winds" and "I Dream'd I Lay".

Proud,

restless, and full of a nameless ambition, the young Burns did his share of

hard work on the farm. His father’s death made him tenant of the farm of

Mossgiel to which the family moved and freed him to seek male and female

companionship where he would. He took sides against the dominant extreme

Calvinist wing of the church in Ayrshire and championed a local gentleman,

Gavin Hamilton, who had got into trouble with the kirk session (a church court)

for Sabbath breaking. He had an affair with a servant girl at the farm,

Elizabeth Paton, who in 1785 bore his first child, and on the child’s birth he

welcomed it with a lively poem.

Tarbolton

Despite

his ability and character, William Burnes was consistently unfortunate, and

migrated with his large family from farm to farm without ever being able to

improve his circumstances. At Whitsun, 1777, he removed his large family from

the unfavourable conditions of Mount Oliphant to the 130-acre (0.53 km2) farm

at Lochlea, near Tarbolton, where they stayed until William Burnes's death in

1784. Subsequently, the family became integrated into the community of

Tarbolton. To his father's disapproval, Robert joined a country dancing school

in 1779 and, with Gilbert, formed the Tarbolton Bachelors' Club the following

year. His earliest existing letters date from this time, when he began making

romantic overtures to Alison Begbie (b. 1762). In spite of four songs written

for her and a suggestion that he was willing to marry her, she rejected him.

Robert

Burns was initiated into the Masonic lodge St David, Tarbolton, on 4 July 1781,

when he was 22. In December 1781, Burns moved temporarily to Irvine to learn to

become a flax-dresser, but during the workers' celebrations for New Year

1781/1782 (which included Burns as a participant) the flax shop caught fire and

was burnt to the ground. This venture accordingly came to an end, and Burns

went home to Lochlea farm. During this time he met and befriended Richard

Brown, who encouraged him to become a poet. He continued to write poems and

songs and began a commonplace book in 1783, while his father fought a legal

dispute with his landlord. The case went to the Court of Session, and Burnes

was upheld in January 1784, a fortnight before he died.

Mauchline

Robert

and Gilbert made an ineffectual struggle to keep on the farm, but after its

failure they moved to Mossgiel Farm, near Mauchline, in March, which they

maintained with an uphill fight for the next four years. In mid-1784 Burns came

to know a group of girls known collectively as The Belles of Mauchline, one of

whom was Jean Armour, the daughter of a stonemason from Mauchline.

Love

affairs

His

first child, Elizabeth "Bess" Burns, was born to his mother's

servant, Elizabeth Paton, while he was embarking on a relationship with Jean

Armour, who became pregnant with twins in March 1786. Burns signed a paper

attesting his marriage to Jean, but her father "was in the greatest distress,

and fainted away". To avoid disgrace, her parents sent her to live with

her uncle in Paisley. Although Armour's father initially forbade it, they were

married in 1788. Armour bore him nine children, three of whom survived infancy.

Burns

had encountered financial difficulties due to his lack of success as a farmer.

In order to make enough money to support a family, he accepted a job offer from

Patrick Douglas, an absentee landowner who lived in Cumnock, to work on his

sugar plantations near Port Antonio, Jamaica. Douglas' plantations were managed

by his brother Charles, and the job offer, which had a salary of £30 per annum,

entailed working in Jamaica as a "book-keeper", whose duties included

serving as an assistant overseer to the Black slaves on the plantations (Burns

himself described the position as being "a poor Negro driver"). The

position, which was for a single man, would entail Burns living on a plantation

in rustic conditions, as it was unlikely a book keeper would be housed in the

plantation's great house. Apologists have argued in Burns' defence that in

1786, the Scottish abolitionist movement was just beginning to be broadly

active. Burns's authorship of "The Slave's Lament", a 1792 poem

argued as an example of his abolitionist views, is disputed. His name is absent

from any abolitionist petition written in Scotland during the period, and

according to academic Lisa Williams, Burns "is strangely silent on the

question of chattel slavery compared to other contemporary poets. Perhaps this

was due to his government position, severe limitations on free speech at the

time or his association with beneficiaries of the slave trade system".

Around

the same time, Burns fell in love with a woman named Mary Campbell, whom he had

seen in church while he was still living in Tarbolton. She was born near Dunoon

and had lived in Campbeltown before moving to work in Ayrshire. He dedicated

the poems "The Highland Lassie O", "Highland Mary", and

"To Mary in Heaven" to her. His song "Will ye go to the Indies,

my Mary, And leave auld Scotia's shore?" suggests that they planned to

emigrate to Jamaica together. Their relationship has been the subject of much

conjecture, and it has been suggested that on 14 May 1786 they exchanged Bibles

and plighted their troth over the Water of Fail in a traditional form of

marriage. Soon afterwards Mary Campbell left her work in Ayrshire, went to the

seaport of Greenock, and sailed home to her parents in Campbeltown. In October

1786, Mary and her father sailed from Campbeltown to visit her brother in

Greenock. Her brother fell ill with typhus, which she also caught while nursing

him. She died of typhus on 20 or 21 October 1786 and was buried there.

Kilmarnock volume

As Burns lacked the funds to pay for his passage to

Jamaica, Gavin Hamilton suggested that he should "publish his poems in the

mean time by subscription, as a likely way of getting a little money to provide

him more liberally in necessaries for Jamaica." On 3 April Burns sent

proposals for publishing his Scotch Poems to John Wilson, a printer in

Kilmarnock, who published these proposals on 14 April 1786, on the same day

that Jean Armour's father tore up the paper in which Burns attested his

marriage to Jean. To obtain a certificate that he was a free bachelor, Burns

agreed on 25 June to stand for rebuke in the Mauchline kirk for three Sundays.

He transferred his share in Mossgiel farm to his brother Gilbert on 22 July,

and on 30 July wrote to tell his friend John Richmond that, "Armour has

got a warrant to throw me in jail until I can find a warrant for an enormous

sum ... I am wandering from one friend's house to another."

On 31 July 1786 John Wilson published the volume of

works by Robert Burns, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect. Known as the

Kilmarnock volume, it sold for 3 shillings and contained much of his best

writing, including "The Twa Dogs" (which features Luath, his Border

Collie), "Address to the Deil", "Halloween", "The

Cotter's Saturday Night", "To a Mouse", "Epitaph for James

Smith", and "To a Mountain Daisy", many of which had been

written at Mossgiel farm. The success of the work was immediate, and soon he

was known across the country.

Burns

postponed his planned emigration to Jamaica on 1 September, and was at Mossgiel

two days later when he learnt that Jean Armour had given birth to twins. On 4

September Thomas Blacklock wrote a letter expressing admiration for the poetry

in the Kilmarnock volume, and suggesting an enlarged second edition. A copy of

it was passed to Burns, who later recalled, "I had taken the last farewell

of my few friends, my chest was on the road to Greenock; I had composed the

last song I should ever measure in Scotland – 'The Gloomy night is gathering

fast' – when a letter from Dr Blacklock to a friend of mine overthrew all my

schemes, by opening new prospects to my poetic ambition. The Doctor belonged to

a set of critics for whose applause I had not dared to hope. His opinion that I

would meet with encouragement in Edinburgh for a second edition, fired me so

much, that away I posted for that city, without a single acquaintance, or a

single letter of introduction."

Development

as a poet

Burns

developed rapidly throughout 1784 and 1785 as an “occasional” poet who more and

more turned to verse to express his emotions of love, friendship, or amusement

or his ironical contemplation of the social scene. But these were not

spontaneous effusions by an almost illiterate peasant. Burns was a conscious

craftsman; his entries in the commonplace book that he had begun in 1783 reveal

that from the beginning he was interested in the technical problems of

versification.

Though

he wrote poetry for his own amusement and that of his friends, Burns remained

restless and dissatisfied. He won the reputation of being a dangerous rebel

against orthodox religion, and, when in 1786 he fell in love with Jean Armour,

her father refused to allow her to marry Burns even though a child was on the

way and under Scots law mutual consent followed by consummation constituted a

legal marriage. Jean was persuaded by her father to go back on her promise.

Robert, hurt and enraged, took up with another woman, Mary Campbell, who died

soon after. On September 3 Jean bore him twins out of wedlock.

Meanwhile,

the farm was not prospering, and Burns, harassed by insoluble problems, thought

of emigrating. But he first wanted to show his country what he could do. In the

midst of his troubles he went ahead with his plans for publishing a volume of

his poems at the nearby town of Kilmarnock. It was entitled Poems, Chiefly in

the Scottish Dialect and appeared on July 31, 1786. Its success was immediate

and overwhelming. Simple country folk and sophisticated Edinburgh critics alike

hailed it, and the upshot was that Burns set out for Edinburgh on November 27,

1786, to be lionized, patronized, and showered with well-meant but dangerous

advice.

The

Kilmarnock volume was a remarkable mixture. It included a handful of first-rate

Scots poems: “The Twa Dogs,” “Scotch Drink,” “The Holy Fair,” “An Address to

the Deil,” “The Death and Dying Words of Poor Maillie,” “To a Mouse,” “To a

Louse,” and some others, including a number of verse letters addressed to

various friends. There were also a few Scots poems in which he was unable to

sustain his inspiration or that are spoiled by a confused purpose. In addition,

there were six gloomy and histrionic poems in English, four songs, of which

only one, “It Was Upon a Lammas Night,” showed promise of his future greatness

as a song writer, and what to contemporary reviewers seemed the stars of the

volume, “The Cotter’s Saturday Night” and “To a Mountain Daisy.”

Burns

selected his Kilmarnock poems with care: he was anxious to impress a genteel

Edinburgh audience. In his preface he played up to contemporary sentimental

views about the “natural man” and the “noble peasant,” exaggerated his lack of

education, pretended to a lack of natural resources, and in general acted a

part. The trouble was that he was only half acting. He was uncertain enough

about the genteel tradition to accept much of it at its face value, and though,

to his ultimate glory, he kept returning to what his own instincts told him was

the true path for him to follow, far too many of his poems are marred by a

naïve and sentimental moralizing.

After

Edinburgh

Edinburgh

unsettled Burns, and, after a number of amorous and other adventures there and

several trips to other parts of Scotland, he settled in the summer of 1788 at a

farm in Ellisland, Dumfriesshire. At Edinburgh, too, he arranged for a new and

enlarged edition (1787) of his Poems, but little of significance was added to

the Kilmarnock selection. He found farming at Ellisland difficult, though he

was helped by Jean Armour, with whom he had been reconciled and whom he finally

married in 1788.

In

Edinburgh Burns had met James Johnson, a keen collector of Scottish songs who

was bringing out a series of volumes of songs with the music and who enlisted

Burns’s help in finding, editing, improving, and rewriting items. Burns was

enthusiastic and soon became virtual editor of Johnson’s The Scots Musical

Museum. Later he became involved with a similar project for George Thomson, but

Thomson was a more consciously genteel person than Johnson, and Burns had to

fight with him to prevent him from “refining” words and music and so ruining

their character. Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum (1787–1803) and the first

five volumes of Thomson’s A Select Collection of Original Scotish Airs for the

Voice (1793–1818) contain the bulk of Burns’s songs. Burns spent the latter

part of his life in assiduously collecting and writing songs to provide words

for traditional Scottish airs. He regarded his work as service to Scotland and

quixotically refused payment. The only poem he wrote after his Edinburgh visit

that showed a hitherto unsuspected side of his poetic genius was “Tam o’

Shanter” (1791), a spirited narrative poem in brilliantly handled

eight-syllable couplets based on a folk legend.

Meanwhile,

Burns corresponded with and visited on terms of equality a great variety of

literary and other people who were considerably “above” him socially. He was an

admirable letter writer and a brilliant talker, and he could hold his own in

any company. At the same time, he was still a struggling tenant farmer, and the

attempt to keep himself going in two different social and intellectual

capacities was wearing him down. After trying for a long time, he finally

obtained a post in the excise service in 1789 and moved to Dumfries in 1791,

where he lived until his death. His life at Dumfries was active. He wrote

numerous “occasional” poems and did an immense amount of work for the two song

collections, in addition to carrying out his duties as exciseman. The outbreak

of the French Revolution excited him, and some indiscreet outbursts nearly lost

him his job, but his reputation as a good exciseman and a politic but

humiliating recantation saved him.

Edinburgh

On

27 November 1786 Burns borrowed a pony and set out for Edinburgh. On 14

December William Creech issued subscription bills for the first Edinburgh

edition of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish dialect, which was published on 17

April 1787. Within a week of this event, Burns had sold his copyright to Creech

for 100 guineas. For the edition, Creech commissioned Alexander Nasmyth to

paint the oval bust-length portrait now in the Scottish National Portrait

Gallery, which was engraved to provide a frontispiece for the book. Nasmyth had

come to know Burns and his fresh and appealing image has become the basis for

almost all subsequent representations of the poet. In Edinburgh, he was

received as an equal by the city's men of letters—including Dugald Stewart,

Robertson, Blair and others—and was a guest at aristocratic gatherings, where

he bore himself with unaffected dignity. Here he encountered, and made a

lasting impression on, the 16-year-old Walter Scott, who described him later

with great admiration:

[His

person was strong and robust;] his manners rustic, not clownish, a sort of

dignified plainness and simplicity which received part of its effect perhaps

from knowledge of his extraordinary talents. His features are presented in Mr

Nasmyth's picture but to me it conveys the idea that they are diminished, as if

seen in perspective. I think his countenance was more massive than it looks in

any of the portraits ... there was a strong expression of shrewdness in all his

lineaments; the eye alone, I think, indicated the poetical character and

temperament. It was large, and of a dark cast, and literally glowed when he

spoke with feeling or interest. [I never saw such another eye in a human head,

though I have seen the most distinguished men of my time.]

The

new edition of his poems brought Burns £400. His stay in the city also resulted

in some lifelong friendships, among which were those with Lord Glencairn, and

Frances Anna Dunlop (1730–1815), who became his occasional sponsor and with

whom he corresponded for many years until a rift developed. He embarked on a

relationship with the separated Agnes "Nancy" McLehose (1758–1841),

with whom he exchanged passionate letters under pseudonyms (Burns called himself

"Sylvander" and Nancy "Clarinda"). When it became clear

that Nancy would not be easily seduced into a physical relationship, Burns

moved on to Jenny Clow (1766–1792), Nancy's domestic servant, who bore him a

son, Robert Burns Clow, in 1788. He also had an affair with a servant girl,

Margaret "May" Cameron. His relationship with Nancy concluded in 1791

with a final meeting in Edinburgh before she sailed to Jamaica for what turned

out to be a short-lived reconciliation with her estranged husband. Before she

left, he sent her the manuscript of "Ae Fond Kiss" as a farewell.

In

Edinburgh, in early 1787, he met James Johnson, a struggling music engraver and

music seller with a love of old Scots songs and a determination to preserve

them. Burns shared this interest and became an enthusiastic contributor to The

Scots Musical Museum. The first volume was published in 1787 and included three

songs by Burns. He contributed 40 songs to volume two, and he ended up

responsible for about a third of the 600 songs in the whole collection, as well

as making a considerable editorial contribution. The final volume was published

in 1803.

Dumfriesshire

Ellisland

Farm

On

his return from Edinburgh in February 1788, he resumed his relationship with

Jean Armour and they married in March 1788. He took out a lease on Ellisland

Farm, Dumfriesshire, settling there in June. He also took up a training

position as an exciseman or gauger, which involved long rides and detailed

bookkeeping. He was appointed to duties in Customs and Excise in 1789. Burns

chose the land of Ellisland a few miles north of the town of Dumfries, from

Patrick Miller's estate at Dalswinton, where he had a new farmhouse and byre

built. He and Jean moved in the following summer 1789 to the new farm house at

Ellisland. In November 1790, he had written his masterpiece, the narrative poem

"Tam O' Shanter". The Ellisland farm beside the river Nith, now holds

a unique collection of Burns's books, artefacts, and manuscripts and is mostly

preserved as when Burns and his young family lived there.[citation needed]

Burns gave up the farm in 1791 to move to Dumfries. About this time he was

offered and declined an appointment in London on the staff of The Star

newspaper, and refused to become a candidate for a newly created Chair of

Agriculture in the University of Edinburgh, although influential friends

offered to support his claims. He did however accept membership of the Royal

Company of Archers in 1792.

Lyricist

After

giving up his farm, he removed to Dumfries. It was at this time that, being

requested to write lyrics for The Melodies of Scotland, he responded by

contributing over 100 songs. He made major contributions to George Thomson's A

Select Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice as well as to James

Johnson's Scots Musical Museum.[citation needed] Arguably his claim to

immortality chiefly rests on these volumes, which placed him in the front rank

of lyric poets. As a songwriter he provided his own lyrics, sometimes adapted

from traditional words. He put words to Scottish folk melodies and airs which

he collected, and composed his own arrangements of the music including

modifying tunes or recreating melodies on the basis of fragments. In letters he

explained that he preferred simplicity, relating songs to spoken language which

should be sung in traditional ways. The original instruments would be fiddle

and the guitar of the period which was akin to a cittern, but the transcription

of songs for piano has resulted in them usually being performed in classical

concert or music hall styles. At the 3 week Celtic Connections festival Glasgow

each January, Burns songs are often performed with both fiddle and guitar.

Thomson

as a publisher commissioned arrangements of "Scottish, Welsh and Irish

Airs" by such eminent composers of the day as Joseph Haydn and Ludwig van

Beethoven, with new lyrics. The contributors of lyrics included Burns. While

such arrangements had wide popular appeal, Beethoven's music was more advanced

and difficult to play than Thomson intended.

Burns

described how he had to master singing the tune before he composed the words:

My

way is: I consider the poetic sentiment, correspondent to my idea of the

musical expression, then chuse my theme, begin one stanza, when that is

composed—which is generally the most difficult part of the business—I walk out,

sit down now and then, look out for objects in nature around me that are in

unison or harmony with the cogitations of my fancy and workings of my bosom,

humming every now and then the air with the verses I have framed. when I feel

my Muse beginning to jade, I retire to the solitary fireside of my study, and

there commit my effusions to paper, swinging, at intervals, on the hind-legs of

my elbow chair, by way of calling forth my own critical strictures, as my, pen

goes.

Burns

also worked to collect and preserve Scottish folk songs, sometimes revising,

expanding, and adapting them. One of the better known of these collections is

The Merry Muses of Caledonia (the title is not Burns's), a collection of bawdy

lyrics that were popular in the music halls of Scotland as late as the 20th

century. At Dumfries, he wrote his world famous song "A Man's a Man for A'

That", which was based on the writings in The Rights of Man by Thomas

Paine, one of the chief political theoreticians of the American Revolution.

Burns sent the poem anonymously in 1795 to the Glasgow Courier. He was also a

radical for reform and wrote poems for democracy, such as – "Parcel of

Rogues to the Nation" and the "Rights of Women".

Many

of Burns's most famous poems are songs with the music based upon older

traditional songs. For example, "Auld Lang Syne" is set to the

traditional tune "Can Ye Labour Lea", "A Red, Red Rose" is

set to the tune of "Major Graham" and "The Battle of

Sherramuir" is set to the "Cameronian Rant".

Political

views

Burns

alienated some acquaintances by freely expressing sympathy with the French, and

American Revolutions, for the advocates of democratic reform and votes for all

men and the Society of the Friends of the People which advocated Parliamentary

Reform. His political views came to the notice of his employers, to which he

pleaded his innocence. Burns met other radicals at the Globe Inn Dumfries. As

an Exciseman he felt compelled to join the Royal Dumfries Volunteers in March

1795.

Failing

health and death

Latterly

Burns lived in Dumfries in a two-storey red sandstone house on Mill Hole Brae,

now Burns Street. The home is now a museum. He went on long journeys on

horseback, often in harsh weather conditions as an Excise Supervisor, and was

kept very busy doing reports. The father of four young children, he was also

frequently occupied as a song collector and songwriter.

As

his health began to give way, he aged prematurely and fell into fits of

despondency. Rumours of intemperance (alleged mainly by temperance activist

James Currie) may have been overstated. Hard manual farm labour earlier in his

life may have damaged Burns' health. Burns possibly had a long-standing

rheumatic heart condition, perhaps beginning when he was 21, and a bacterial

infection, possibly arising from a tooth abcess, may have exacerbated this.

On

the morning of 21 July 1796, Burns died in Dumfries, at the age of 37.

The

funeral took place on Monday 25 July 1796, the day that his son Maxwell was

born. He was at first buried in the far corner of St. Michael's Churchyard in

Dumfries; a simple "slab of freestone" was erected as his gravestone

by Jean Armour, which some felt insulting to his memory. His body was

eventually moved to its final location in the same cemetery, the Burns

Mausoleum, in September 1817. The body of his widow Jean Armour was buried with

his in 1834.

After

Burns death

Armour

had taken steps to secure his personal property, partly by liquidating two

promissory notes amounting to fifteen pounds sterling (about 1,100 pounds at

2009 prices). The family went to the Court of Session in 1798 with a plan to

support his surviving children by publishing a four-volume edition of his

complete works and a biography written by James Currie. Subscriptions were

raised to meet the initial cost of publication, which was in the hands of

Thomas Cadell and William Davies in London and William Creech, bookseller in

Edinburgh. Hogg records that fund-raising for Burns's family was embarrassingly

slow, and it took several years to accumulate significant funds through the

efforts of John Syme and Alexander Cunningham.

Burns

was posthumously given the freedom of the town of Dumfries. Hogg records that

Burns was given the freedom of the Burgh of Dumfries on 4 June 1787, 9 years

before his death, and was also made an Honorary Burgess of Dumfries.

Through

his five surviving children (of 12 born), Burns has over 900 living descendants

as of 2019.

Poetical

Career

Throughout

his life Robert Burns was also a practicing poet. His poetry recorded and

celebrated aspects of farm life, regional experience, traditional culture,

class culture and distinctions, and religious practice. He is considered the

national poet of Scotland. Although he did not set out to achieve that

designation, he clearly and repeatedly expressed his wish to be called a Scots

bard, to extol his native land in poetry and song, as he does in “The Answer”:

Ev’n

thena wish (I mind its power)

A

wish, that to my latest hour

Shall

strongly heave my breast;

That

I for poor auld Scotland’s sake

Some

useful plan, or book could make,

Or

sing a sang at least.

And

perhaps he had an intimation that his “wish” had some basis in reality when he

described his Edinburgh reception in a letter of December 7, 1786 to his friend

Gavin Hamilton: “I am in a fair way of becoming as eminent as Thomas a Kempis

or John Bunyan; and you may expect henceforth to see my birthday inserted among

the wonderful events, in the Poor Robin’s and Aberdeen Almanacks. … and by all

probability I shall soon be the tenth Worthy, and the eighth Wise Man, of the

world.”

That

he is considered Scotland’s national poet today owes much to his position as

the culmination of the Scottish literary tradition, a tradition stretching back

to the court makars, to Robert Henryson and William Dunbar, to the 17th-century

vernacular writers from James VI of Scotland to William Hamilton of

Gilbertfield, to early 18th-century forerunners such as Allan Ramsay and Robert

Fergusson. Burns is often seen as the end of that literary line both because

his brilliance and achievement could not be equaled and, more particularly,

because the Scots vernacular in which he wrote some of his celebrated works

was—even as he used it—becoming less and less intelligible to the majority of

readers, who were already well-versed with English culture and language. The

shift toward English cultural and linguistic hegemony had begun in 1603 with

the Union of the Crowns when James VI of Scotland became James I of Great

Britain; it had continued in 1707 with the merging of the Scottish and English

Parliaments in London; and it was virtually a fait accompli by Burns’s day save

for pockets of regional culture and dialect. Thus, one might say that Burns

remains the national poet of Scotland because Scottish literature ceased with

him, thereafter yielding poetry in English or in Anglo-Scots or in imitations

of Burns.

Burns,

however, has been viewed alternately as the beginning of another literary

tradition: he is often called a pre-Romantic poet for his sensitivity to

nature, his high valuation of feeling and emotion, his spontaneity, his fierce

stance for freedom and against authority, his individualism, and his

antiquarian interest in old songs and legends. The many backward glances of

Romantic poets to Burns, as well as their critical comments and pilgrimages to

the locales of Burns’s life and work, suggest the validity of connecting Burns

with that pervasive European cultural movement of the late 18h and early 19th

centuries which shared with him a concern for creating a better world and for

cultural renovation.

Nonetheless,

the very qualities which seem to link Burns to the Romantics were logical

responses to the 18th-century Scotland into which he was born. And his humble,

agricultural background made him in some ways a spokesperson for every Scot,

especially the poor and disenfranchised. He was aware of humanity’s unequal

condition and wrote of it and of his hope for a better world of equality

throughout his life in epistle, poem, and song—perhaps most eloquently in the

recurring comparison of rich and poor in the song “For A’ That and A’ That,”

which resoundingly affirms the humanity of the honest, hard-working, poor, man:

“The Honest man, though e’er sae poor, / Is king o’ men for a’ that.”

Burns

is an important and complex literary personage for several reasons: his place

in the Scottish literary tradition, his pre-Romantic proclivities, his position

as a human being from the less-privileged classes imaging a better world. To

these may be added his particular artistry, especially his ability to create

encapsulating and synthesizing lines, phrases, and stanzas which continue to

speak to and sum up the human condition. His recurring and poignant hymns to

relationships are illustrative, as in the lines from the song beginning “Ae

fond Kiss”:

Had

we never lov’d sae kindly,

Had

we never lov’d sae blindly!

Never

met—or never parted,

We

had ne’er been broken-hearted.

The

Scotland in which Burns lived was a country in transition, sometimes in

contradiction, on several fronts. The political scene was in flux, the result

of the 1603 and 1707 unions which had stripped Scotland of its autonomy and

finally all but muzzled the Scottish voice, as decisions and directives issued

from London rather than from Edinburgh. A sense of loss led to questions and

sometimes to actions, as in the Jacobite rebellions early in the 18th century.

Was there a national identity? Should aspects of Scottish uniqueness be

collected and enshrined? Should Scotland move ahead, adopting English manners,

language, and cultural forms? No single answer was given to any of these

questions. But change was afoot: Scots moved closer to an English norm, particularly

as it was used by those in the professions, religion, and elite circles; “think

in English, feel in Scots” seems to have been a widespread practice, which

limited the communicative role, as well as the intelligibility, of Scots. For a

time, however, remnants of the Scots dialect met with approbation among certain

circles. A loose-knit movement to preserve evidences of Scottish culture

embraced products that had the stamp of Scotland upon them, lauding Burns as a

poet from the soil; assembling, editing, and collecting Scottish ballads and

songs; sometimes accepting James Macpherson’s Ossianic offerings; and lauding

poetic Jacobitism. This movement was both nationalistic and antiquarian,

recognizing Scottish identity through the past and thereby implicitly accepting

contemporary assimilation.

Perhaps

the most extraordinary transition occurring between 1780 and 1830 was the

economic shift from agriculture to industry that radically altered social

arrangements and increased social inequities. While industrialization finished

the job agricultural changes had set the transition in motion earlier in the

18th century. Agriculture in Scotland had typically followed a widespread

European form known as runrig, wherein groups of farmers rented and worked a

piece of land which was periodically re-sub-divided to insure diachronic if not

synchronic equity. Livestock was removed to the hills for grazing during the

growing season since there were no enclosures. A subsistence arrangement, this

form of agriculture dictated settlement patterns and life possibilities and was

linked inextricably to the ebb and flow and unpredictable vicissitudes of the

seasons. The agricultural revolution of the 18th century introduced new crops,

such as sown grasses and turnips, which made wintering over of animals

profitable; advocated enclosing fields to keep livestock out; developed new

equipment—in particular the iron plow—and improved soil preparation; and

generally suggested economies of scale. Large landowners, seeing profit in making

“improvements,” displaced runrig practices and their adherents, broadening the

social and economic gap between landowner and former tenant; the latter

frequently became a farm worker. Haves and have-nots became more clearly

delineated; “improvements” depended on capital and access to descriptive

literature. Many small tenant farmers foundered during the transition,

including both Burnes and his father.

Along

with the gradual change in agriculture and shift to industry there was a

concomitant shift from rural to urban spheres of influence. The move from Scots

to greater reliance on English was accelerated by the availability of cheap

print made possible by the Industrial Revolution. Print became the medium of

choice, lessening the power of oral culture’s artistic forms and aesthetic

structures; print, a visual medium, fostered linear structures and perceptual

frameworks, replacing in part the circular patterns and preferences of the oral

world.

Two

forces, however, served to keep change from being a genuine revolution and made

it more nearly a transformation by fits and starts: the Presbyterian church and

traditional culture. Presbyterianism was established as the Kirk of Scotland in

1668. Although fostering education, the printed word, and, implicitly, English

for specific religious ends, and thus seeming to support change, religion was

largely a force for constraint and uniformity. Religion was aided but

simultaneously undermined by traditional culture, the inherited ways of living,

perceiving, and creating. Traditional culture was conservative, preferring the

old ways—agricultural subsistence or near subsistence patterns and oral forms

of information and artistry conveyed in customs, songs, and stories. But if

both religion and traditional culture worked to maintain the status quo,

traditional culture was finally more flexible: as inherited, largely oral

knowledge and art always adapting to fit the times, traditional culture was

less rigid. It was diverse and it celebrated freedom.

Scotland’s

upheavals were in many ways Burns’s upheavals as well: he embraced cultural

nationalism to celebrate Scotland in poem and song; he struggled as a tenant

farmer without the requisite capital and know-how in the age of “improvement”;

he combined the oral world of his childhood and region with the education his

father arranged through an “adventure school”; he accepted, but resented, the

moral judgments of the Kirk against himself and friends such as Gavin Hamilton;

he knew the religious controversies which pitted moderate against conservative

on matters of church control and belief; he reveled in traditional culture’s

balladry, song, proverbs, and customs. He was a man of his time, and his

success as poet, songwriter, and human being owes much to the way he responded

to the world around him. Some have called him the typical Scot, Everyman.

Burns

began his career as a local poet writing for a local, known audience to whom he

looked for immediate response, as do all artists in a traditional context. He

wrote on topics of appeal both to himself and to his artistic constituency,

often in a wonderfully appealing conversational style.

Burns’s

early life was spent in the southwest of Scotland, where his father worked as

an estate gardener in Alloway, near Ayr. Subsequently William Burnes leased

successively two farms in the region, Mount Oliphant nearby and Lochlie near

Tarbolton. Between 1765 and 1768 Burns attended an “adventure” school

established by his father and several neighbors with John Murdock as teacher,

and in 1775 he attended a mathematics school in Kirkoswald. These formal and

more or less institutionalized bouts of education were extended at home under

the tutelage of his father. Burns was identified as odd because he always

carried a book; a countrywoman in Dunscore, who had seen Burns riding slowly

among the hills reading, once remarked, “That’s surely no a good man, for he

has aye a book in his hand!” The woman no doubt assumed an oral norm, the

medium of traditional culture.

Life

on a pre-or semi-improved farm was backbreaking and frequently heartbreaking,

since bad weather might wipe out a year’s effort. Bad seed would not prosper

even in the best-prepared soil. Rain and damp, though necessary for crop

growth, were often “too much of a good thing.” Burns grew up knowing the

vagaries of farming and understanding full well both mental preparation and

long days of physical labor. His father had married late and was thus older

than many men with a household of children; he was also less physically

resilient and less able to endure the tenant farmer’s lot. Bad seed and rising

rents at various times spelled failure to his ventures. At the time of his

approaching death and a disastrous end to the Lochlie lease, Burns and his

brother secretly leased Mossgiel Farm near Mauchline. Burns was 25.

The

death of his father, the family’s patriarchal force for constraint in religion,

education, and morality, freed Burns. He quickly became recognized as a rhymer,

sometimes signing himself after the farm as Rab Mossgiel. The midwife’s prophecy

at his birth—that he would be much attracted to the lasses—became a reality; in

1785 he fathered a daughter by Betty Paton, and in 1786 had twins by Jean

Armour. His fornications and his thoughts about the Kirk, made public, opened

him to church censure, which he bore but little accepted. It was almost as

though the floodgates had burst: his poetic output between 1784 and 1786

includes many of those works on which his reputation stands—epistles, satires,

manners-painting, and songs—many of which he circulated in the manner of the

times: in manuscript or by reading aloud. Many works of this period,

judiciously chosen to appeal to a wider audience, appeared in the first formal

publication of his work, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, printed in Kilmarnock

in 1786 and paid for by subscriptions.

The

Kilmarnock edition might be seen as the result of two years or so of riotous

living: much conviviality, much socializing with women in an era before birth

control, much thinking about humanity without the “correcting” restraint of the

paterfamilias, much poetry and song ostensibly about the immediate environment

but encapsulating aspects of the human condition. All of this was certainly

more interesting than the agricultural round, which offered a physical constraint

to match the moral and mental constraint of religion. Both forms of constraint

impeded the delight in life that many of Burns’s finest works exhibit.

Furthermore, he was in serious trouble with the Armour family, who destroyed a

written and acceptable, if a bit unorthodox, marriage contract. He resolved to

get out of town quickly and to leave behind something to prove his worth. He

seems to have made plans to immigrate to the West Indies, and he brought to

fruition his plan to publish some of his already well-received works. One of

the 612 copies reached Edinburgh and was perceived to have merit. Informed of

this casual endorsement, Burns abandoned his plans for immigration—if they had

ever been serious—and left instead for Edinburgh.

The

Kilmarnock edition shows Burns’s penchant for self-presentation and his ability

to choose variable poses to fit the expectations of the intended receiver.

Burns presents himself as an untutored rhymer, who wrote to counteract life’s

woes; he feigns anxiety over the reception of his poems; he pays tribute to the

genius of the Scots poets Ramsay and Fergusson; and he requests the reader’s

indulgence. In large measure, the material belies the tentativeness of the

preface, revealing a poet aware of his literary tradition, capable of building

on it, and deft in using a variety of voices—from “couthie” and colloquial,

through sentimental and tender, to satiric and pointed. But the book also

contains evidence of Burns as local poet, turning life to verse in slight,

spur-of-the-moment pieces, occasional rhymes made on local personages, often to

the gratification of their enemies. The Kilmarnock edition, however, is more

revealing for its illustration of his place in a literary tradition: “The

Cotter’s Saturday Night,” for example, echoes Fergusson’s “The Farmer’s Ingle”

(1773); “The Holy Fair” is part of a long tradition of peasant brawls, drawing

on a verse form, the Chrystis Kirk stanza, known by the name of a

representative poem attributed to James I: “Chrystis Kirk of the Grene.” Many

of Burns’s poems and verse epistles employ the six-line stanza, derived from

the medieval tail-rhyme stanza which was used in Scotland by Sir David Lindsay

in Ane Satyre of the Thrie Estaitis (1602) but was probably seen by Burns in

James Watson’s Choice Collection (1706-1711) in works by Hamilton of

Gilbertfield and Robert Sempill of Beltrees; Sempill’s “The Life and Death of

Habbie Simpson” gave the form its accepted name, Standard Habbie. Quotations

from and allusions to English literary figures and their works appear

throughout his work: Thomas Gray in “The Cotter’s Saturday Night,” Alexander

Pope in “Holy Willie’s Prayer,” John Milton in “Address to the Deil.”

Poems,

Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (an undistinguished title used often before and

after as a title of local poets’ effusions) was a success. With all its obvious

contradictions—untutored but clearly lettered; peasant but perspicacious;

conscious national pride (“The Vision,” “Scotch Drink”) together with multiple

references to other literatures—the Kilmarnock edition set the stage for

Burns’s success in Edinburgh and anticipated his conscious involvement in the

cultural nationalistic movement. Such works as “Address to the Deil” anticipate

this later concern:

O

Thou, whatever title suit theee!

Auld

Hornie, Satan, Nick, or Clootie,

Wha

in you cavern grim an’ sooty

Clos’d

under hatches,

Spairges

about the brunstane cootie,

To

scaud poor wretches!

Hear

me, auld Hangie, for a wee,

An’

let poor, damned bodies bee;

I’m

sure sma’ pleasure it can gie,

Ev’n

to a deil,

To

skelp an’ scaud poor dogs like me,

An’

hear us squeel!

These

two stanzas provide evidence of the implicit tension between established

religion and traditional culture rampant in Burns’s early work. Burns takes his

epigraph from Milton—

O

Prince, O chief of many throned pow’rs,

That

led th’ embattl’d Seraphim to war—

conjuring

up biblical ideas of Satan as fallen angel, hell as a place of fire and

damnation, the devil as punisher of evil. But Burns’s deil, familiarly

addressed, is an almost comic, ever-present figure, tempting humanity but

escapable. Burns allies him with traditional forces—spunkies, waterkelpies—and

gives old Clootie no more force or power. Traditional notions of the devil are

much less restraining than the formal religious concepts. By juxtaposing Satan

and Auld Nickie, Burns conjures up metaphorically the two dominant cultural

forces—one for constraint and the other for freedom. Here as elsewhere in

Burns’s work, freedom reigns.

Burns’s

affection for traditional culture is amply illustrated. In a well-known

autobiographical letter to Dr. John Moore (August 2, 1787) he pays tribute to

its early influence when he says, “In my infant and boyish days too, I owed

much to an old Maid of my Mother’s, remarkable for her ignorance, credulity and

superstition.—She had, I suppose, the largest collection in the county of tales

and songs concerning devils, ghosts, fairies, brownies, witches, warlocks,

spunkies, kelpies, elf-candles, dead-lights, wraiths, apparitions, cantraips,

giants, inchanted towers, dragons and other trumpery.—This cultivated the

latent seeds of Poesy.”

Burns’s

first and last works were songs, reflecting his deep connection with oral

ballad and song. The world of custom and belief is most particularly described

in “Halloween,” an ethnographic poem with footnotes elucidating rural customs.

Many forms of prognostication are possible on this evening when this world and

the other world or worlds hold converse, a time when unusual things are deemed

possible—especially foretelling one’s future mate and status. Burns’s notes and

prefatory material have often been used as evidence of his distance from and

perhaps disdain for such practices. Yet the poem itself is peopled with a

sympathetic cast of youths, chaperoned by an old woman, joined together for fun

and fellowship. The youthful players try several prognosticatory rites in

attempting to anticipate their future love relationships. In one stanza Burns

alludes to a particular practice—“pou their stalks o’ corn”—and explains in his

note that “they go to the barn-yard, and pull each, at three several times, a

stalk of Oats. If the third stalk wants the top-pickle, that is, the grain at

the top of the stalk, the party in question will come to the marriage-bed any thing

but a Maid.” Burns concludes the stanza by saying that one Nelly almost lost

her top-pickle that very night. Some of the activities in what is essentially a

preliminary courtship ritual are frightening, requiring collective daring.

Burns describes the antics, anticipation, and anxieties of the participants as

they enjoy the communal event, which is concluded with food and drink:

Wi’

merry sangs, an’ friendly cracks,

I

wat they did na weary;

And

unco tales, an’ funnie jokes,

Their

sports were cheap an’ cheary:

Till

buttr’d So’ns, wi’ fragrant lunt,

Set

a’ their gabs a steerin;

Syne,

wi’ a social glass o’ strunt,

They

parted aff careerin

Fu’

blythe that night.

“The

Cotter’s Saturday Night” is on one level a microcosmic description of the

agricultural, social, and religious practices of the farm worker—albeit an

idealized vision that reiterates Burns’s absolute affection for traditional

aspects of life, a fictive version of his own experience. The poem is a

celebration of the family and of the lives of simple folk, sanitized of

hardship, crop failure, sickness, and death. Burns achieves this vision by

focusing on a moment of domestic repose of a family reunited in love and

affection. The Master and Mistress are the architects of the family circle;

Jenny and “a neebor lad” seem destined to provide continuity. The gathering

concludes with family worship: songs are sung and Scripture is read, including

biblical accounts of human failings by way of warning. The domestic celebration

of religion within the context of traditional life is noble and good.

From

Scenes like these, old SCOTIA’S grandeur springs,

That

makes her lov’d at home, rever’d abroad:

Princes

and lords are but the breath of kings,

‘An

honest man’s the noble work of GOD.’

This

poem was lauded largely because of its linguistic accessibility, as a pastoral

expression of nationalism, a symbolic representation of the “soul of Scotland.”

Auguste Angellier offers critical affirmation: “Never has the existence of the

poor been invested with so much dignity.” The lowly farm worker is depicted as

the ideal Scot. The cotter’s good life was already an anachronism, so Burns’s

depiction in this early poem is antiquarian, backward-looking, and imbued with

cultural nationalism—perspectives which became intensified and focused in his

later work. But by 1784-1785 his work was already engaged in dialogue with

larger cultural issues. The linguistic attributes of the poem become part of

this conversation as Burns modulates from Scots into Scots English to English,

poetically reflecting the dichotomy of feeling and thinking. The stability of

life as described in this poem is a wonderful accommodation of traditional

culture and religion; celebration of belief in God follows naturally from

sharing a way of life. But the religion that is here applauded is domestic and

familial. Institutional religion Burns saw as something quite other.

Institutional

religion at its worst is excessively hierarchical, constraining, and above all

unjust, damning some and saving others. As a child Burns was steeped in the

doctrine of predestination and effectual calling, which asserts that some

people are “elected” by God to be saved without any consideration of life and

works; the unchosen are damned no matter what they do. Carried to an extreme,

the doctrine would permit an individual who felt assured of election to do all

manner of evil, a scenario developed in Burns’s “Holy Willie’s Prayer.” Burns

could not accept the orthodox position of the so-called Auld Lichts; he

believed in the power of good works to determine salvation. His corner of

Scotland was a bastion of conservative religious position and practice: the

Kirk session served as a moral watchdog, summoning congregants who strayed from

the “straight and narrow” and handing out censure and punishment.

Thus

religion was a cultural force with which to contend. Burns participated in the

debate through poetry, circulating his material orally and in manuscript. Chief

among his works in this vein is the satire “Holy Willie’s Prayer.” Prompted by

the defeat of the Auld Licht censure of his friend Hamilton for failure to

participate in public worship, the poem, shaped like a prayer, is put into the

mouth of the Auld Licht adherent Holy Willie. It begins with an effective

invocation which articulates Willie’s doctrinal stance on predestination in

Standard Habbie:

O

Thou that in the heavens does dwell!

Wha,

as it pleases best thysel,

Sends

ane to heaven an ten to h-ll,

A’

for thy glory!

And

no for ony gude or ill

They’ve

done before thee.

The

poem continues with Willie’s thanks for his own “elected” status and reaches

its highest moments in Willie’s confession that “At times I’m fash’d wi’

fleshly lust.” Burns has Willie condemn himself by describing moments of

fornication and justifying them as temptations visited on him by God. The

concluding stanzas recount Willie’s opinion of Hamilton—“He drinks, and swears,

and plays at cartes”—and his chagrin that Minister Auld was defeated. The poem

ends with the requisite petition, calling for divine vengeance on those who

disagree with him and asking blessings for himself and his like. Burns condemns

both the doctrine and the practice of institutional religion.

The

tensions between religion and traditional culture are particularly obvious in

“The Holy Fair.” Burns’s depiction of an open-air communion gathering, with

multiple sermons and exhortations, includes an important subtext on the

sociability of food, drink, chat, and perhaps love—attractions which will lead

to behavior decried in sermons that very day. Again religious constraint and

traditional license meet, with freedom clearly preferable:

How

monie hearts this day converts,

O’

Sinners and o’ Lasses!

Their

hearts o’ stane, gin night are gane

As

saft as ony flesh is.

There’s

some are fou o’ love divine;

There’s

some are fou o’ brandy;

An’

monie jobs that day begin,

May

end in Houghmagandie

Some

ither day.

“The

Jolly Beggars; or, Love and Liberty: A Cantata” goes even further toward

affirming freedom through traditional culture. Probably written in 1785 but not

published until after Burns’s death, this work combines poetry and song to

describe a joyful gathering of society’s rejects: the maimed and physically

deformed, prostitutes, and thieves. The work alternates life histories with

narrative passages describing the convivial interaction of the social outcasts.

Despite their low status, the accounts they give of their lives reveal an

unrivaled ebullience and joy. The texts are wedded to traditional and popular

tunes. The choice of tunes is not random but underlines the characteristics and

experiences described in the words: thus the tinker describes his occupation to

the woman he has seduced away from a fiddler to the tune “Clout the Caudron,”

whose traditional text describes an itinerant fixer of pots and pans, that is,

a seducer of women. The assembled company exhibits acceptance of their lots in

life, an acceptance made possible because their positions are shared by all

present and by the power of drink to soften hardships. Stripped of all the

components of human decency, lacking religious or material riches, the beggars

are jolly through drink and fellowship, rich in song and story—traditional

pastimes. The cantata rushes to a riotous conclusion in which those assembled

sing a rousing countercultural chorus that would certainly have received Holy

Willie’s harshest censure:

A

fig for those by LAW protected,

LIBERTY’s

a glorious feast!

COURTS

for Cowards were erected,

CHURCHES

built to please the Priest.

“The

Jolly Beggars” implicitly speaks to the economic situation of the time: more

and more people were made jobless and homeless in the rush for “improvement,”

and the older pattern of taking care of the parish poor had broken down because

of greater mobility and greater numbers of needy. Burns offers no solution, but

he does illustrate the beggars’ humanity and, above all, their capacity for

Life with a capital L—a mode of behavior that is convivial; unites people in

story, song, and drink; and exudes delight and joy: traditional culture wins

again.

Burns

worked out in poetry some of his responses to his own culture by showing

opposing views of how life should be lived. Descriptions of his own experiences

stimulated musings on constraint and freedom. Critical tradition says that John

Richmond and Burns observed the beggars in Poosie Nansie’s “The Holy Fair” may

be based on the Mauchline Annual Communion, which was held on the second Sunday

of August in 1785; the gathering of the cotter’s family may not describe a

specific event but certainly depicts a generalized and typical picture. Thus

Burns’s own experiences became the base from which he responded to and

considered larger cultural and human issues.

The

Kilmarnock edition changed Burns’s life: it sprang him away for a year and a

half from the grind of agricultural routine, and it made him a public figure.

Burns arrived in the capital city in the heyday of cultural nationalism, and

his own person and works were hailed as evidences of a Scottish culture: the

Scotsman as a peasant, close to the soil, possessing the “soul” of nature; the

works as products of that peasant, in Scots, containing echoes of earlier

written and oral Scottish literature.

Burns

went to Edinburgh to arrange for a new edition of his poems and was immediately

taken up by the literati and proclaimed a remarkable Scot. He procured the

support of the Caledonian Hunt as sponsors of the Edinburgh edition and set to

work with the publisher William Creech to arrange a slightly altered and

expanded edition. He was wined and dined by the taste-setters, almost without

exception persons from a different class and background from his. He was the

“hit” of the season, and he knew full well what was going on: he intensified

aspects of his rural persona to conform to expectations. He represented the

creativity of the peasant Scot and was for a season “Exhibit A” for a distinct

Scottish heritage.

Burns

used this time for a variety of experiments, trying on several roles. He

entered into what seems to have been a platonic dalliance with a woman of some

social standing, Agnes McLehose, who was herself in an ambiguous social

situation—her husband having been in Jamaica for some time. The relationship,

whatever its true nature, stimulated a correspondence, in which Burns and Mrs.

McLehose styled themselves Sylvander and Clarinda and wrote predictably

elevated, formulaic, and seemingly insincere letters. Burns lacks conviction in

this role; but he met more congenial persons: boon companions, males whom he

joined in back-street howffs for lively talk, song, and bawdry.

If

the Caledonian Hunt represented the late-18th-century crème de la crème, the

Crochallan Fencibles, one of the literary and convivial clubs of the day in

which members took on assumed names and personae, represented the middle ranks

of society where Burns felt more at home. In the egalitarian clubs and howffs

Burns met more sympathetic individuals, among them James Johnson, an engraver

in the initial stages of a project to print all the tunes of Scotland. That

meeting shifted Burns’s focus to song, which became his principal creative form

for the rest of his life.

The

Edinburgh period provided an interlude of potentiality and experimentation.

Burns made several trips to the Borders and Highlands, often being received as

a notable and renowned personage. Within a year and a half Burns moved from

being a local poet to one with a national reputation and was well on his way to

being the national poet, even though much of his writing during this period

continued an earlier versifying strain of extemporaneous, occasional poetry.

But the Edinburgh period set the ground-work for his subsequent creativity,

stimulated his revealing correspondence, and provided him with a way of

becoming an advocate for Scotland as anonymous bard.

If

Burns were received in Edinburgh as a typical Scot and a producer of genuine

Scottish products, that cultural nationalism in turn channeled his love of his

country—already expressed in several poems in the Kilmarnock edition—into his

songs. Burns’s support for Johnson’s project is infectious; in a letter to a

friend, James Candlish, he wrote in November 1787: “I am engaged in assisting

an honest Scots Enthusiast, a friend of mine, who is an Engraver, and has taken

it into his head to publish a collection of all our songs set to music, of which

the words and music are done by Scotsmen.—This, you will easily guess, is an

undertaking exactly to my taste.—I have collected, begg’d, borrow’d and stolen

all the songs I could meet with.—Pompey’s Ghost, words and music, I beg from

you immediately.” Here was a chance to do what he had been doing all his

life—wedding text and tune—but for Scotland. Thus Burns became a conscious

participant in the antiquarian and cultural movement to gather and preserve

evidences of Scottish identity before they were obliterated in the cultural

drift toward English language and culture. Burns’s clear preference for

traditional culture, and particularly for the freedom it represented, shifted

intensity and direction because of the Edinburgh experience. He narrowed his focus

from all of traditional culture to one facet—song. Balladry and song were safe

artifacts that could be captured on paper and sanitized for polite edification.

This approach to traditional culture was distanced and conscious, while his

earlier depiction of the larger whole of traditional culture had been

immediate, intimate, and largely unconscious. Thus Edinburgh changed his

artistic stance, making him more clearly aware of choices and directions as

well as a conscious antiquarian.

In

all, Burns had a hand in some 330 songs for Johnson’s The Scots Musical Museum

(1787-1803), a six-volume work, and for George Thomson’s five-volume A Select

Collection of Original Scottish Airs for the Voice (1793-1818). As a

nationalistic work, The Scots Musical Museum was designed to reflect Scottish

popular taste; like similar publications, it included traditional songs—texts

and tunes—as well as songs and tunes by specific authors and composers. Burns

developed a coded system of letters for identifying contributors, suggesting to

all but the cognoscenti that the songs were traditional. It is often difficult

to separate Burns’s work from genuinely traditional texts; he may, for example,

have edited and polished the old Scots ballad “Tam Lin,” which tells of a man

restored from fairyland to his human lover. Many collected texts received a

helping hand—fragments were filled out, refrains and phrases were amalgamated

to make a whole—and original songs in the manner of tradition were created

anew. Burns’s song output was enormous and uneven, and he knew it: “Here, once

for all, let me apologies for many silly compositions of mine in this work.

Many beautiful airs wanted words.” Yet many of the songs are succinct

masterpieces on love, on the brotherhood of man, and on the dignity of the

common man—subjects which link Burns with oral and popular tradition on the one

hand and on the other with the societal changes that were intensifying

distinctions between people.

Perhaps

the most remarkable thing about Burns’s songs is their singability, the

perspicacity with which words are joined to tune. “My Love she’s but a lassie

yet” provides a superb example: a sprightly tune holds together four loosely

connected stanzas about a woman, courtship, drink, and sexual dalliance to

create a whole much greater than the sum of the parts. The Song begins:

My

love she’s but a lassie yet,

My

love she’s but a lassie yet;

We’ll

let her stand a year or twa,

She’ll

no be half sae saucy yet.

It

concludes, enigmatically:

We’re

a’ dry wi’ drinking o’t,

We’re

a’ dry wi’ drinking o’t:

The

minister kisst the fidler’s wife,

He

could na preach for thinkin o’t.—

The

songs are at their best when sung, but there may be delight in text alone, for

brilliant stanzas appear most unexpectedly. The chorus of “Auld Lang Syne”

encapsulates the pleasure of reunion, of shared memory:

For

auld lang syne, my jo,

For

auld lang syne,

We’ll

tak a cup o’ kindness yet

For

auld lang syne.

The

vignette of a couple aging together—“We clamb the hill the gither” in “John

Anderson My Jo” suggests praise of continuity and shared lives. In a similar

manner “A Red, Red Rose“ depicts a love that is both fresh and lasting: “O my

Luve’s like a red, red rose, / That’s newly sprung in June.”

Burns’s

comment in a letter to Mrs. Dunlop of Dunlop in 1790—“Old Scots Songs are, you

know, a favorite study and pursuit of mine”—accurately describes his absorption

with song after Edinburgh. He not only collected, edited, and wrote songs but

studied them, perusing the extant collections, commenting on provenance,

gathering explanatory material, and speculating on the distinct qualities of

Scottish song: “There is a certain something in the old Scots songs, a wild

happiness of thought and expression” and of Scottish music: “let our National

Music preserve its native features.—They are, I own, frequently wild, &

unreduceable to the more modern rules; but on that very eccentricity, perhaps,

depends a great part of their effect.” This nationalism did not stop with song

but pervaded all Burns’s work after Edinburgh. Certainly the most critically

acclaimed product of this period is a work written for Francis Grose’s

Antiquities of Scotland (1789-1791). Burns suggested Alloway Kirk as a subject

for the work and wrote “Tam o’ Shanter” to assure its inclusion.

“Tam

o’ Shanter” is the culmination of Burns’s delight in traditional culture and

his selective elevation of parts of that culture in his antiquarian and

nationalistic pursuit of Scottish distinctness. The poem retells a legend about

a man who comes upon a witches’ Sabbath and unwisely comments on it, alerting

the participants to his presence and necessitating their revenge. Burns

provides a frame for the legend, localizes it at Alloway Kirk, and peoples it

with plausible characters—in particular, the feckless Tam, who takes every

opportunity to imbibe with his buddies and avoid going home to wife and

domestic responsibilities. Tam stops at a tavern for a drink and sociability

and gets caught up in the flow of song, story, and laughter; the raging storm

outside makes the conviviality inside the tavern doubly precious. But it is

late and Tam must go home and “face the music,” having yet again gotten drunk,

no doubt having used money intended for less selfish and more basic purposes.

On his way home Tam experiences the events which are central to the legend; the

initial convivial scene has provided the context in which such legends might be

told. After passing spots enshrined in other legends, he comes upon the

witches’ Sabbath revels at the ruins of Alloway Kirk, with the familiar and not

quite malevolent devil, styled “auld Nick,” in dog form playing bagpipe

accompaniment to the witches’ dance. Burns incorporates skeptical

interpolations into the narrative—perhaps Tam is only drunk and “seeing

things”—which replicate in poetic form aspects of an oral telling of legends.

And the concluding occurrence of Tam’s escapade, the loss of his horse’s tail

to the foremost witch’s grasp, demands a response from the reader in much the

same way a legend told in conversation elicits an immediate response from the

listener. Burns, then, has not only used a legend and provided a setting in

which legends might be told but has replicated poetically aspects of a verbal

recounting of a legend. And he has used a traditional form to celebrate Scotland’s

cultural past. “Tam o’ Shanter” may be seen as Burns’s most mature and complex

celebration of Scottish cultural artifacts.

If

there were a shift of emphasis and attitude toward traditional culture as a

result of the Edinburgh experience, there was also continuity. Early and late

Burns was a rhymer, a versifier, a local poet using traditional forms and

themes in occasional and sometimes extemporaneous productions. These works are

seldom noteworthy and are sometimes biting and satiric. He called them “little

trifles” and frequently wrote them to “pay a debt.” These pieces were not

thought of as equal to his more deliberate endeavors; they were play,

increasingly expected of him as a poet. He probably would have disavowed many

now attributed to him, particularly some of the mean-spirited epigrams. Several

occasional pieces, however, deserve a closer look for their ability to raise

the commonplace to altogether different heights.

In

1786 Burns wrote “To a Haggis,” a paean to the Scottish pudding of seasoned

heart, liver, and lungs of a sheep or calf mixed with suet, onions, and oatmeal

and boiled in an animal’s stomach:

Fair

fa’ your honest, sonsie face,

Great

Chieftan o’ the Puddin-race!

Aboon

them a’ ye tak your place,

Painch,

tripe, or thairm:

Weel

are ye wordy of a grace

As

lang’s my arm.

Varying

accounts claim that the poem was created extempore, more or less as a blessing,

for a meal of haggis. Burns’s praise has contributed to the elevation of the

haggis to the status of national food and symbol of Scotland. Less well known

and dealing with an even more pedestrian subject is “Address to the

Tooth-Ache,” prefaced “Written by the Author at a time when he was grievously

tormented by that Disorder.” The poem is a harangue, delightfully couched in

Standard Habbie, beginning: “My curse on your envenom’d stang, / That shoots my

tortur’d gums alang,” a sentiment shared by all who have ever suffered from

such a malady.

The

many songs, the masterpiece “Tam o’ Shanter,” and the continuation and

profusion of ephemeral occasional pieces of varying merit all stand as

testimony to Burns’s artistry after Edinburgh, albeit an artistry dominated by

a selective, focused celebration of Scottish culture in song and legend. This

narrowing of focus and direction of creativity suited his changed situation.

Burns left Edinburgh in 1788 for Ellisland Farm, near Dumfries, to take up

farming again; on August 5 he legally wed Jean Armour, with whom he had seven

more children. For the first time in his life he had to become respectable and

dependable. Suddenly the carefree life of a bachelor about town ended (although